Stories

Watchers on the Land

In 1998 a young soldier named Philip Cheung travelled to Nunavut to learn survival skills from the Canadian Rangers, a unique sub-component of the Army Reserve in the North. Nineteen years later, Cheung—now a seasoned combat photojournalist—returned to the Arctic to document the role of the Rangers in the contested and rapidly changing region.

Text — Mark Mann

Photos — Philip Cheung

When most people think of war photography, they picture dramatic shots of soldiers in action, not quiet landscapes, subdued portraits, or delicate still-life compositions. Philip Cheung is one of the rare photographers able to work at the crossroads where art and photojournalism meet. Leaving aside the spectacle of battle, Cheung instead fixes his lens on the deeper context of militarized environments, searching out the ways that space and atmosphere can reveal truths that normally stay outside of the frame.

Cheung is based in LA but grew up in Toronto. When he was 17 a recruiter from the Canadian Armed Services came to his high school, and Cheung signed up for the infantry. He enlisted for all the familiar reasons: to see the world, learn new skills, and have adventures.

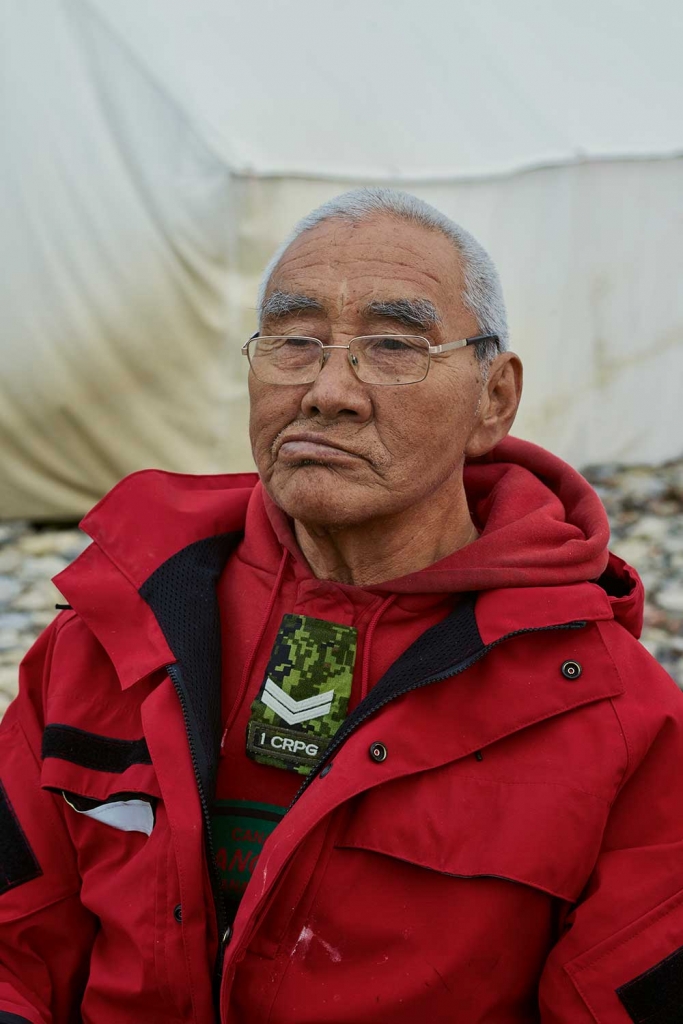

Cheung’s military service soon led him in an unexpected direction. In 1998 his training took him to Gjoa Haven, Nunavut, to learn survival skills from the Canadian Rangers, a unique sub-component of the Army Reserve in the Arctic comprising some 5,000 people spread out in more than 200 communities across the North. Tasked by the Canadian military to perform surveillance, search and rescue, and disaster response, the Rangers, about half of whom are Inuit, also undertake annual training missions with new recruits like Cheung. The soldiers share military tactics and weapons training, and in turn they learn survival skills from the Rangers, like fishing, foraging, and hunting—all the way from stalking and shooting to butchering and cooking a caribou. Apart from practical skills, the Rangers also share lessons in their history, language, philosophy, and way of life.

Rangers help pull a boat ashore after a severe storm at Ujarasugjuligaarjuk Point.

After that first trip, Cheung went on to serve a six-month tour in Bosnia as a peacekeeper, where he began documenting his time in the infantry on disposable Kodak cameras. Returning to Canada, this seed of interest in taking pictures soon blossomed into a career in photography, and his experience as a soldier ultimately gave him the confidence to go back into combat zones as an embedded photojournalist in Afghanistan and Iraq.

As he freelanced throughout the Middle East for five years, Cheung became fascinated by similarities between the desert and the terrain he’d seen in the North. “The landscape is eerily similar in some parts of Afghanistan to some parts of the Arctic in summer,” he says. “The dirt is the same colour; the tundra is the same colour.” When he finally returned to North America, he applied for the Canadian Forces Artist Program, which enabled him to return to the same communities he’d visited as a young soldier. In 2017 Cheung flew to the community of Taloyoak in Nunavut to join a patrol that would take him around King William Island, travelling in small boats from Matheson Point to Gjoa Haven and then on to Simpson Strait, and lastly, to Ujarasugjuligaarjuk Point.

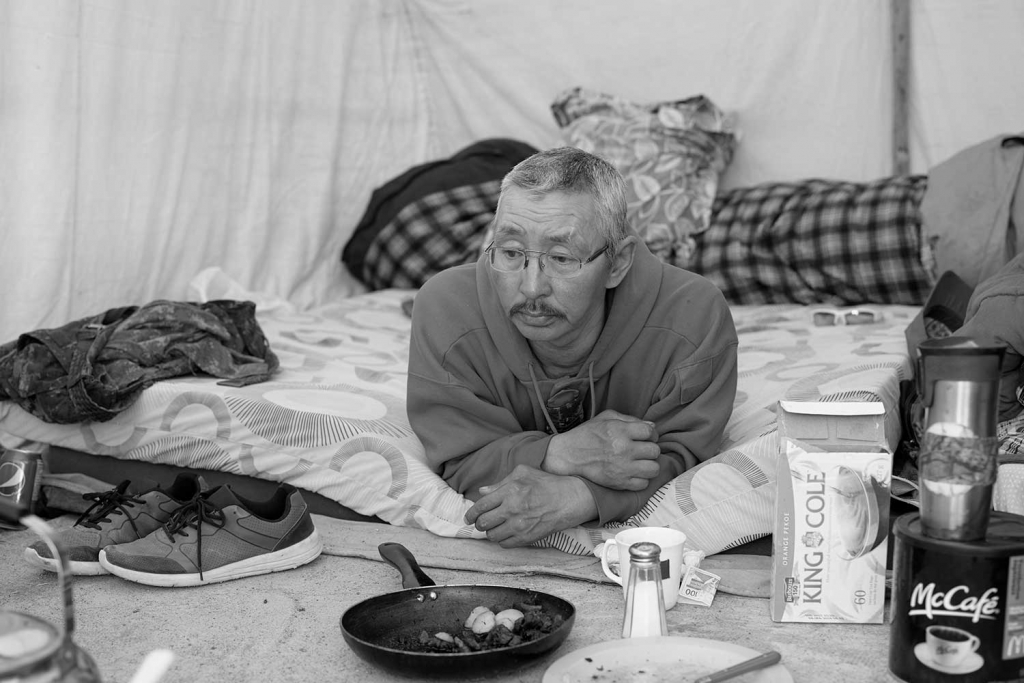

Back in the North for the second time, Cheung tagged along with a troop of soldiers in training as they joined the Rangers for military exercises out on the land. The resulting series, Arctic Front, offers a meditation on the complex reciprocity between traditional land-based cultures and armed forces in the age of climate change. The images are poignant, but they also acquire an anxious tension when viewed in light of the sovereignty concerns that now weigh heavily on the North.

The Arctic is increasingly becoming a contested space, as Russia is building up its military capabilities there and both China and the U.S. are positioning to play a greater role in the region. Experts believe the threat of a Russian or Chinese land invasion is extremely remote, however. Much of the international interest focuses on the emergence of new shipping lanes and commercial fisheries as the ice melts, along with the potential opening of vast tracts of the Arctic seabed to oil and gas extraction. Scientists predict the entire Arctic Ocean could be ice-free in summer by 2035.

Prior to going on a patrol, all Rangers sight in their rifles and are tested on their marksmanship skills.

Though war is the theoretical backdrop, the Rangers don’t tend to talk about combat. “I didn’t meet any Rangers who were expecting a Russian invasion,” Cheung says. “The major concerns for many that I spoke to were global warming, the increase in traffic and shipping traffic in the North, the melting of the ice, and the migration patterns of animals.” For the Inuit, it’s simply harder to get food. They have to go further and further out from their communities to hunt, making the local knowledge they’ve depended on for so long suddenly unreliable.

Still, the Rangers’ motto is “Vigilans,” which means “the watchers,” and according to the Government of Canada, their job is to “conduct and provide support to sovereignty operations.” In practice, each patrol goes out on one lengthy exercise each year to do things like check infrastructure like remote runways and radar stations. Each of these trips begins and ends with a parade on ATVs, attended by the entire community, who wish them luck and celebrate their return. The Rangers also gather intelligence organically as they are out hunting and fishing on the land. They will report back to the military when they spot unusual sea or air traffic, for example, and in the last few years, they have been coming across more and more solo adventurers in sailboats, often stranded by harsh weather.

***

People who see his photos of the Rangers tend to draw disparate conclusions about the group and its role in the North, Cheung says. Some view it positively, commenting on how important they are to Canada and the North by blending their traditional way of life with the military and passing their knowledge to the younger generation. “But on the other side, there’s the thought that Canada can’t protect its borders . . . What are a few thousand people in red hoodies going to do in case of a military invasion from Russia?” Cheung encourages people to draw their own judgments.

Whatever the wider perception, the resourcefulness of the Rangers is beyond doubt. Cheung experienced this first-hand when the patrol he joined in 2017 was stranded on what was supposed to be the last day of their exercises on the land. They woke up on the shores of Ujarasugjuligaarjuk Point to find the water too choppy and dangerous to risk embarking. For four days they were stranded, soon running short on food and water. The Rangers sprang into action, quickly locating a pond of fresh water left over from the previous winter’s freeze and hunting caribou and seal to eat. “Things got real,” says Cheung. “This is where their expertise came and saved us all.”

Ranger Keith Poodlat drinks from a stream at Malerualik Lake.

Arctic Front brims with an energy that is both casual and stately. Cheung achieves this effect through a form of planned serendipity: “A lot of the landscape work I do, you have to anticipate certain moments, so you have to incorporate the photojournalism aspect with your landscape work,” he says. Working on a tripod, he hunts out scenes where he thinks something might happen, composes his shot, and then waits for whatever will unfold. “I really need to think one step ahead to where someone might go or walk through the frame.” In this way, the images acquire a spontaneity that is also timeless—a fitting tribute for the willing and ready Rangers and their time-honoured craft of living off the land. ■

Never Miss Another Issue

Two issues per year

25% OFF previous issues

Free Shipping in Canada