Livraison gratuite au QC / 15% de rabais pour 3 items / 25% pour 4 / 30% pour 5 et +

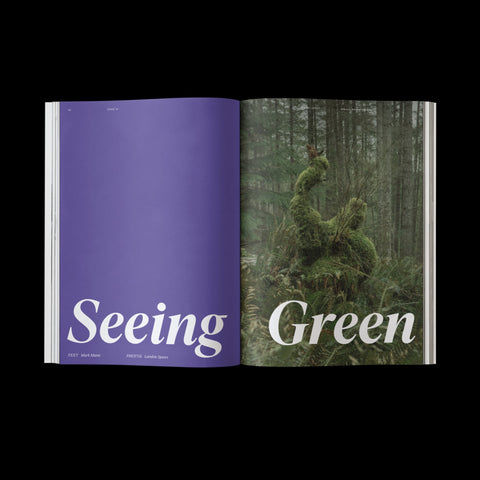

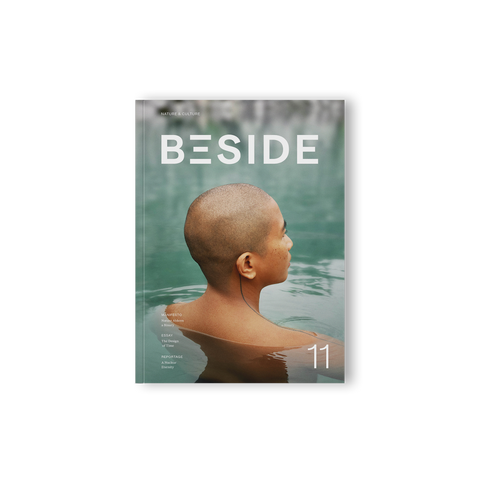

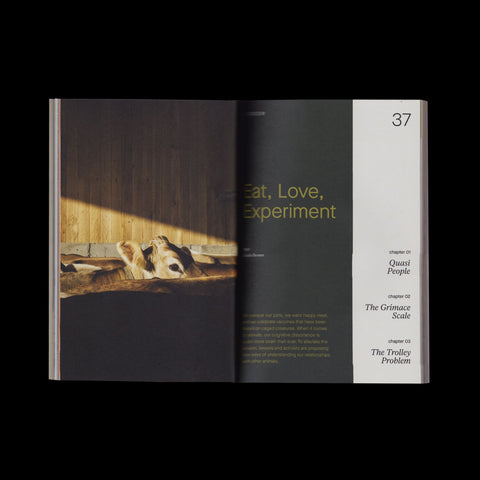

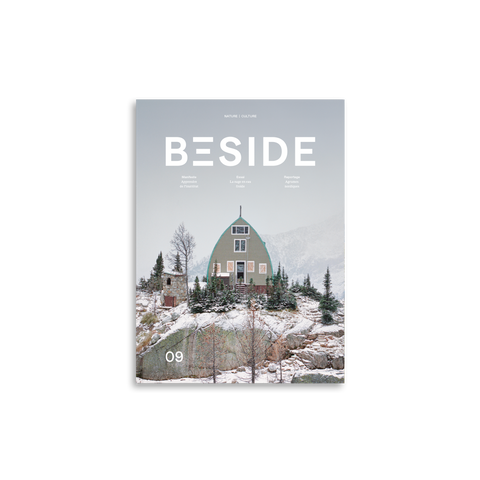

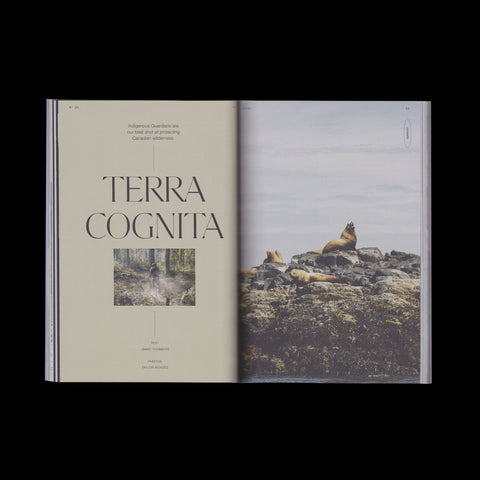

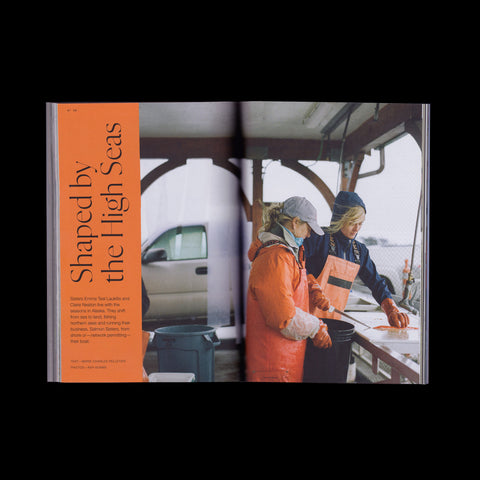

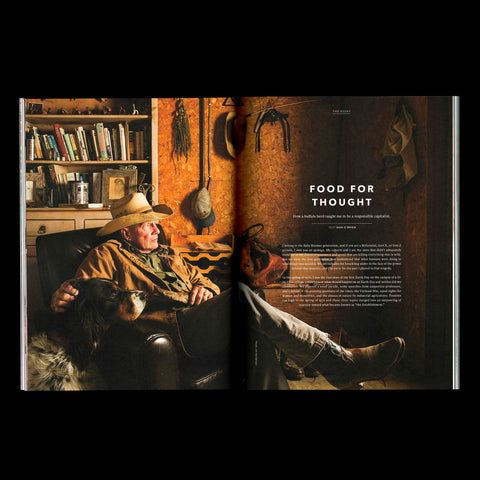

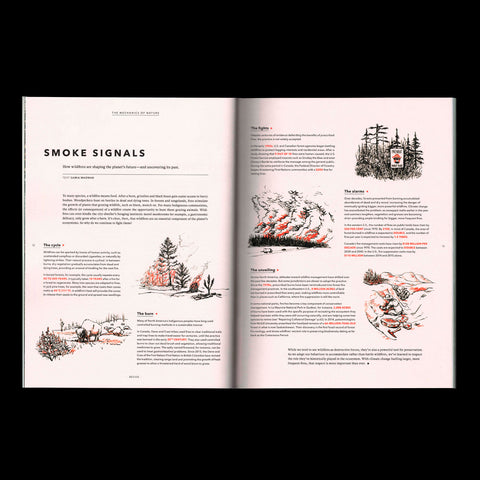

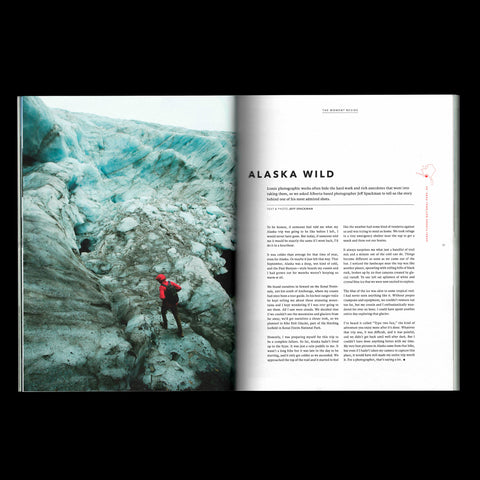

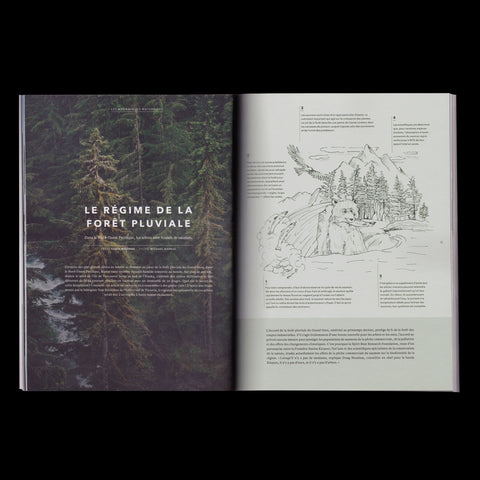

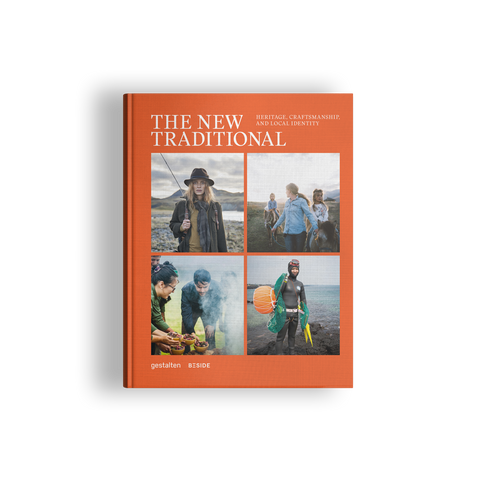

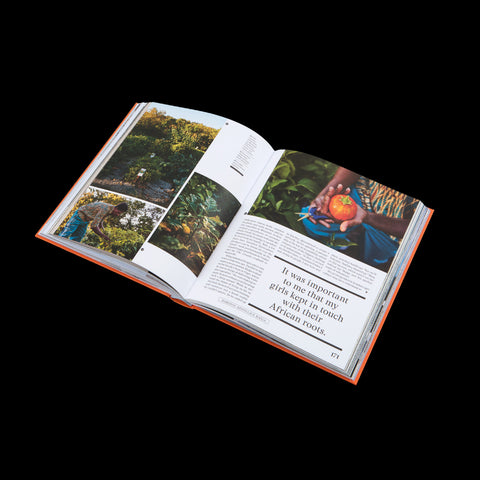

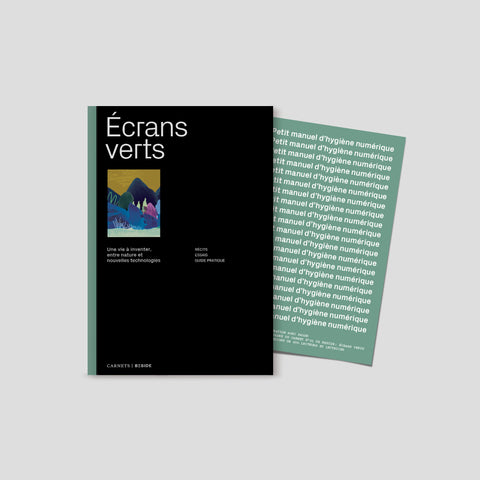

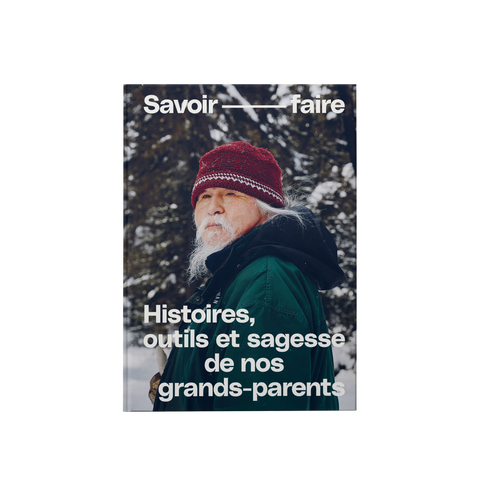

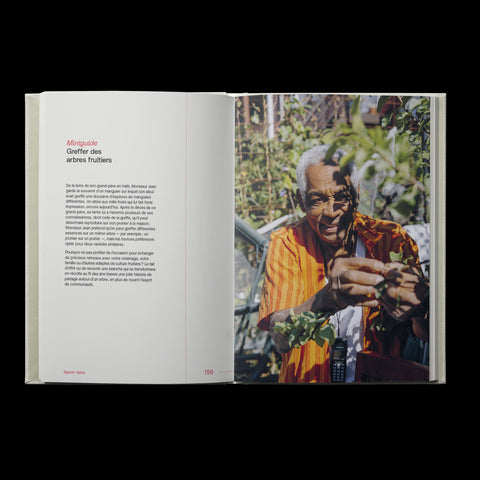

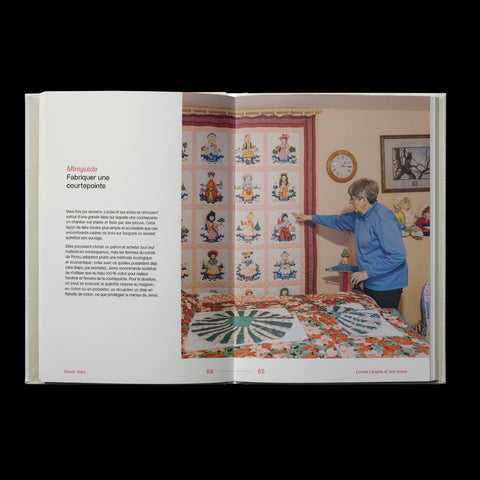

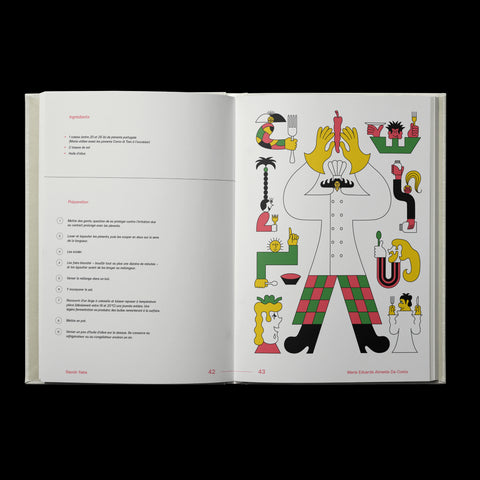

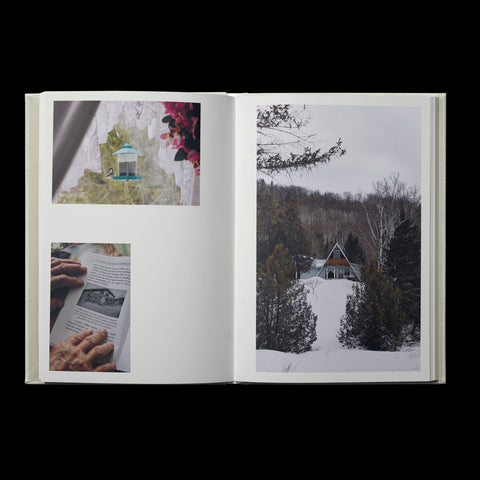

Là où nature et culture se rencontrent

Pensée comme une extension de notre univers, la Collection BESIDE rassemble des objets durables et porteurs de sens. Chaque pièce incarne un design intentionnel, enraciné dans le vivant, pour enrichir le quotidien avec simplicité, beauté et une connexion plus profonde au monde qui nous entoure.