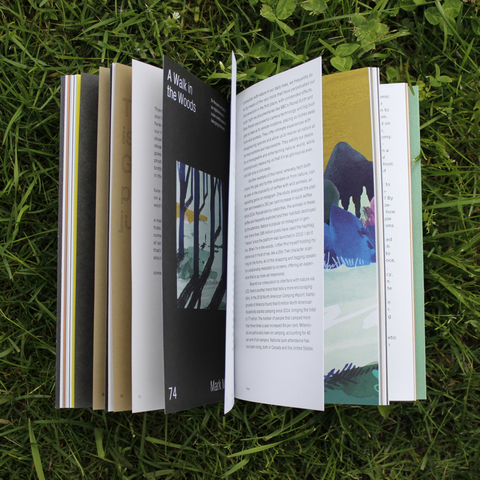

Because natural environments are plentiful and free, we often forget what they're really worth.

TEXT: Guillaume Rivest

ILLUSTRATION: Geoffrey Holstad

Nature is not merely magnificent. It also provides important ecosystem “balancing” services, contributing to, among other things, climate control, water purification, and the circulation of nutrients in the soil. And because the state does not have to pay for those projects undertakes, many environmentalists, economists, and legislators are often tasked to quantify in dollars just how much these natural processes save the annual budget.

New York City’s drinking water provides one of the most telling examples. Since rainwater is naturally filtered via the Catskill Mountains' watershed, when the Safe Drinking Water Act made it mandatory for states to filter water intended for public consumption in 1976, New York was granted an exemption, which came into effect in 1997. To protect this area against real estate and industrial development—and maintain its exceptional status—the State has had to mobilize activists, city councils, and governmental agencies collaboratively for 20 years. Of the one billion gallons of drinking water consumed daily by New York City residents in 2016, 90 per cent was supplied naturally by the Catskills.

By protecting the natural environments that create this localized watershed, New York State has saved more than US $12 billion so far; as building a filtration plant would have cost US $6 billion, and its operation costs are estimated at US $300 million annually (since 1997!). And don't forget, this water filtration service only represents one of the ecosystem services that New York State could have picked in its fight to protect the watershed.

New York City’s drinking water provides one of the most telling examples. Since rainwater is naturally filtered via the Catskill Mountains' watershed, when the Safe Drinking Water Act made it mandatory for states to filter water intended for public consumption in 1976, New York was granted an exemption, which came into effect in 1997. To protect this area against real estate and industrial development—and maintain its exceptional status—the State has had to mobilize activists, city councils, and governmental agencies collaboratively for 20 years. Of the one billion gallons of drinking water consumed daily by New York City residents in 2016, 90 per cent was supplied naturally by the Catskills.

By protecting the natural environments that create this localized watershed, New York State has saved more than US $12 billion so far; as building a filtration plant would have cost US $6 billion, and its operation costs are estimated at US $300 million annually (since 1997!). And don't forget, this water filtration service only represents one of the ecosystem services that New York State could have picked in its fight to protect the watershed.

In 2008, the United Nations estimated that the total value of ecosystem services that nature provides to the entire planet amounts to between US $21 and 72 trillion—thus comparable to the world's gross domestic product (GDP), which amounts to approximately US $58 trillion. Yet while it does fosters a certain awareness of the ways nature affects us beyond immediate comprehension, the monetization of ecosystem services is a dangerous and somewhat limited exercise. Is economic value the only one that counts? Is it better to preserve an ecosystem that provides us with services or an ecosystem that's disappearing? Do we really understand ecosystem interdependence? An economic assessment is certainly a way to recognize an ecosystem’s value, but it's important to remember that our choices have consequences that often reach beyond our understanding of the issues involved.