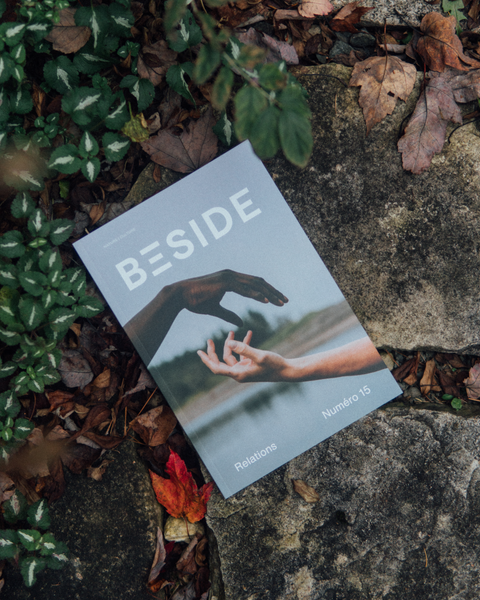

At the foot of the mountain in Bromont, Noah Forand runs fast but grows up slowly and a little differently than others. Without knowing it, he’s teaching his family and friends l’art de vivre.

TEXT: Marie Charles Pelletier

PHOTOS: Marc-Antoine Forand

Noah Forand was born in summer 2016 in Cowansville, with almond-shaped eyes, brown hair, and a smaller-than-normal palate.

His parents, Carolanne and Marc-Antoine, don’t notice anything amiss at first; they're immersed in the overflowing love they feel for their new baby. When a nurse comes to visit them at home a few days after the birth, she notices that Noah is having trouble swallowing. She sends the three of them to the hospital for some tests.

Three days go by, far too slowly.

In the car that finally takes them to the doctor’s office, their hearts tremble. Carolanne thinks back to the results of her first-trimester nuchal translucency ultrasound exam. The back of the baby’s neck had been slightly enlarged. But the blood samples and other tests were perfectly normal. A procedure known as amniocentesis could have shed more light, but it wasn't recommended because it increases the risk of miscarriage. Somehow, the remote possibility that her child might have Down syndrome had never really left the mind of this mother-to-be.

They reach the end of the 15 km trip. The diagnosis is delivered, and their hearts break.

Eyes swollen, bodies emptied of sobs, the new parents confer. There’s only one thing to do: get informed. Beyond physical differences, they know nothing about Down syndrome. On that day, they learn that Noah has an extra chromosome shaped like a hat that added itself without warning to his 21st pair of chromosomes. They also learn that Down syndrome is not an illness, but a congenital condition which can indeed lead to health problems, but doesn’t always.

In Québec, 90 per cent of women choose to abort when they receive this diagnosis. Many women complain about a lack of support from the health-care system when the time comes to make this decision. In Carolanne and Marc-Antoine’s case, since it was a surprise, they didn’t face this dilemma during pregnancy or dread what was to come. “I would never judge a family that decided to end a pregnancy, but the best advice I can give to a woman who learns she’s pregnant with a child with Down syndrome is to meet some people who have it before making her decision. To go meet families and get to know the kids,” says Carolanne.

Only 40 years ago, young mothers whose babies carried the additional chromosome were advised to give the child up for adoption upon birth. Today, we call this little chromosome the “happiness gene,” because those who have it often display a pure and joyful way of living.

Despite this, hospitals still regularly offer adoption papers to the parents of a child with Down syndrome, as though the connection was automatic. The diagnosis is scary at first, with increased risks of a variety of issues. But statistics don’t show the beauty of children who are “beyond average,” or what their differences have to teach us on a daily basis. These things are hard to convey in a tri-fold leaflet.

Shortly after Noah’s birth, the Regroupement pour la Trisomie 21 support group put Carolanne and Marc-Antoine in contact with a number of other families also dealing with this difference. “It was when we met people with Down syndrome and other parents going through the same thing as us that we realized this might not be a tragedy. That it might just be a different path toward happiness,” says Carolanne, while June, their two-year-old daughter, babbles in the background.

Of course they still have worries. Will Noah know how to express himself? Will he have friends? Will he be invited to other kids’ parties? Will he go to regular school? Will he play hockey in the street with his uncles and cousins? Of course they still have trouble sleeping sometimes, and of course the first years are filled with a series of appointments and follow-ups at the ergonomist, the physiotherapist, the ophthalmologist, and the speech therapist.

In truth, what keeps them up at night is not worry that Noah might not pass mathematics one day, but the hope that he will be able to carve out a little place for himself in society. And so they’ve chosen to fight for Noah not to be defined by his Down syndrome.

The Little Buddha

After the birth of his little sister, Noah’s family visited the East Coast. Sitting in the sand, Noah watches the tide come in, waves breaking over the shore and receding, flowing back out into the openness. For two hours, he watches the water. It’s the first time he has seen the ocean.

Noah is happiest outside. He’s all eyes and ears, watching and listening, attentive for long stretches. He loves walking quietly on the mountain beside their small city, or sitting in the grass with an animal he’s especially fond of, like Café, his grandmother’s dog.

Particularly sensitive to emotions, Noah is able to read the feelings of other people easily and seems to feel everything more strongly than others. If he’s feeling shy, he says it out loud (this was the first thing he said to me when he saw me in the doorway!). If his father appears worried, Noah asks him what’s wrong. He’s deeply concerned about others’ well-being, and he is never elsewhere in his mind. He is fully present, all the time. He doesn’t need a YouTube tutorial or to analyze Dead Poets’ Society to understand the essence of “seize the day.” It’s innate in him. He appreciates each moment that passes and each of the people who share his existence.

Noah enjoys time alone. He often sits down and crosses his legs, as though to contemplate life. If his mother happens to bother him when he’s in this meditative state, he looks at her and gently says, “Mama, be quiet,” with a little gesture of his hand. “You’d think he was here to teach us to focus on what matters,” his parents say.

We should note that in addition to inadvertently teaching mindfulness, Noah also runs. A lot. And fast. It may be because he’s been seeing his father leave the house with running shoes on ever since he was very small, returning each time with full lungs and a calm mind.

Running for Noah

Marc-Antoine started running shortly after Noah’s birth. He runs to think, or to stop thinking. He runs to find his inner compass and to calm his anxiety. The distances have grown as the years have gone by. But during the pandemic, his races were cancelled one after another. This was when Marc-Antoine got the idea: he would run for Noah. His plan was to run for 21 consecutive hours on June 21st, the summer solstice, and raise money for Regroupement pour la Trisomie 21. In 2021, for the second edition, he ran 250 km through the mountains over five days. Carolanne and Marc-Antoine initially hoped to raise $400, but word spread and people’s hearts were touched. In the end, they donated over $25,000 to the organization.

“The money we raised will allow other parents like us to have access to lower-cost health services with the help of the Regroupement. Because appointments are expensive and can weigh heavily on a parent’s bank account,” explains Marc-Antoine. These appointments with experts help children in their development, so they can learn to speak, to walk, and possibly become independent one day.

Running wasn’t something Marc-Antoine had always done. Each time he went out, he learned to push his limits further, one stride at a time. Without knowing it, Noah had taught his father resilience. And Marc-Antoine, in return, only wants to know that his son is happy — that he’s playing, that he’s riding his bécyk [bike], that he can run if he wants to, and that he often proves all predictions wrong.

What really counts in this family is to have a great day. Not to become captain of the soccer team or to win a medal at the end-of-year gala. “At night, we go to bed asking if everyone is happy. If the answer is yes, we can sleep soundly,” smiles Marc-Antoine.

The eyes of the heart

“I remember feeling scared to tell my brother when he came to see me at the hospital, because I was afraid he wouldn’t love Noah as much as I love his kids. I was scared for Noah, for what awaited him . . . at daycare, at school, in the street: scared that the way other people looked at him would hurt,” says Carolanne.

Although Carolanne was afraid when the diagnosis was delivered, five years later she realizes how lucky she is to be able to raise a child with different abilities. Our society is still far from perfect, but it has never been as inclusive of diverse experiences of being.

The more we stop ignoring or hushing up differences, the more we can learn to appreciate shades and nuances. The time has come to speak with our children, our friends, and our neighbours about the importance of difference and inclusion. This doesn’t simply mean accepting that everyone has a place at the table; it also means recognizing the unique gifts they each bring. After all, what would a dinner party be if everyone was always talking about the same thing?

If Carolanne could speak to the mother she was five years ago, she would tell her to look for the people who can see the beauty in Noah, and to keep them close.

Being a parent doesn’t mean insisting that your child see the world as you do, according to your experience of existence. It means having the chance to see life through new eyes. Sometimes it means simply sitting down, legs crossed, and watching the tide come in.