New Narratives

“My parents had fled the war, and here I was running right back to it.”

Jad Haddad, who grew up in Lebanon during wartime, has long since been attracted to war zones. Today he is the head of an adventure tourism agency, fulfilling his quest for discovery and the unknown differently.

I’ve always had a hard time with limits. When I would go out riding my bike as a kid, my mother would always ask me not to go past the stop signs at either end of our street, but I’d never listen. It was as if something beyond them was calling me and I couldn’t help it. Deep down, without realizing it, I was already living for adventure.

I had just turned 5 when my parents and I immigrated to Canada. We got here in 1989, in the dead of winter. I don’t remember the cold, but I do remember the long tree-lined street that led all the way from Mirabel Airport to Fabreville, the small neighbourhood of Laval where my maternal grandparents had purchased a family home near a field. That was home for us, even if we moved around a lot afterward. I know it was wintertime because I had started watching the Montréal Canadiens on TV. They lost the Stanley Cup that year, but they still made me want to take up hockey. And I’ve been playing ever since.

On the other hand, I remember very little about Lebanon at that time. I grew up in a town called Zahlé, a kind of verdant oasis in the Beqaa Valley, halfway between Beirut and Damascus. Due to its location, it was a strategic outpost between the two countries, and the target of countless attacks during the Lebanese Civil War. That’s what my parents and I were leaving behind in 1989, just when the fighting was about to end but the future still looked dim.

The memory of our departure is still clear in my mind. The whole family coming together to say goodbye. The crowded dinner table, the chargrilled dishes, the colourful plates of tabbouleh and fattoush, arak flowing freely—the Lebanese are never short of reasons to enjoy extravagant meals—and then the journey to Damascus through the mountains to catch our flight to Montréal.

War was never really something talked about at our house, even though it had a constant presence. Like in many Lebanese homes, war had a face and a name: my uncle’s, my mother’s brother, who died in a bombing. Years later and thousands of kilometres away, his photograph is a daily reminder of his loss—and of our story. But war isn’t always black and white when it comes to emotions, and I have always had a fascination with it… beyond my family background and despite my parents’ concerns.

I took photography in Cegep. I figured that might be the key to finding my answers. I was completely obsessed with warzone journalism, I dreamt of working for Magnum Photos, I binge-watched documentaries, I devoured books, I practiced by attending protests… I was looking for action.

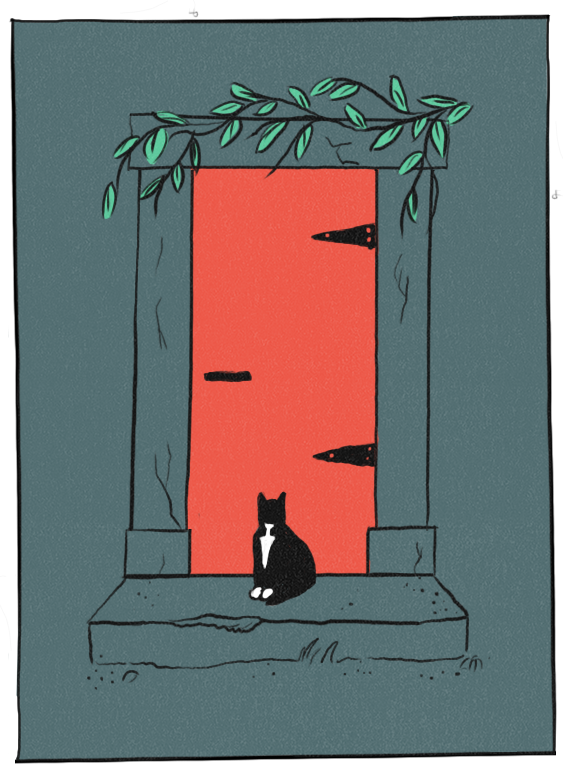

It’s around then that I returned to Lebanon for the first time. I was 19 years old, and I felt like I was walking through a waking dream. Everything was so strangely familiar, it was as though I’d never left—or never really left. I remember taking a picture of a cat in front of a cellar door on one of my town’s little streets. My mother told me some time later that she and some other women had hidden behind that very door during the bombings. The last few times, she was pregnant with me.

My father’s family had also lived there, and still lives there to this day. But as usual, no one wanted to talk to me about the war, or show me any remnants of it. And I understood: that conflict had literally robbed an entire generation of its childhood. So I tried to make my way and go it alone. For me, it was the chance to try out some photojournalism; to push past the stop sign at the end of the street once more. It took some doing, though!

My parents had fled the war, and here I was running right back to it.

When I got back, an organization from Concordia University that did humanitarian work in Uganda approached my friend and I to shoot a documentary about child soldiers. And so, off I went again: we were based in Kampala for nearly five months, in the heart of the country, less than 180 miles [300 km] from yet another civil war. In retrospect, there I was again: blindly seeking adventure without fully realizing the potential consequences of risk taking, trial and error, and impromptu encounters. Once, we took a motorcycle taxi up to a refugee camp in the north of the country. We’d had to negotiate our right of passage with the army in order to get there… This was my first encounter with emergency humanitarian assistance.

The experience taught me how to face my weaknesses: I realized that I didn’t always have the tools needed to fully understand the topics that interest me, or those which I seek to cover. So I made the decision to go back to school to study political science and international relations, all while going out in the field to shoot or fundraising in support of the organizations that worked in war zones.

This persistent desire to go away for even longer, to travel even further, was still alive and well. Seven years ago, I had taken all the necessary steps to go off and join Doctors Without Borders in the Republic of the Congo. I was ready this time: I had experience, knowledge, and an understanding of their needs. But in the end, I didn’t go—my heart tipped the scales and I chose to stay put.

On the other hand, later when I was offered my first adventure tourism contract, I said yes immediately without thinking.

I quickly realized that while I could point out areas of conflict on a map, I had no clue where the travel spots were.

The word adventure took on a new meaning that year, far from war and humanitarianism.

Today I’m the Director of Terres d’Aventure Canada. Each trek and every expedition is my teacher. The world—from the tops of the Atlas Mountains in Morocco to the cedar forests of Japan, through the desolate Icelandic interior and the dense jungles of Colombia to the abundant shores of Saguenay Fjord—opened itself up to me in a totally new way: people and their stories had always been my life’s theme, but now they coexisted with breathtaking experiences and landscapes that were larger than life.

I still run on risk, but now they’re calculated ones. That said, the unknown is still a strong driving force. I have a thirst for discoveries, thrills, and as always, flexible limits. I’ve just come back from a trek in Antarctica, and this time I’m sure, it was without a doubt the farthest I’ve ventured past the stop signs on my street.