Portrait

The great animal choir

Bernie Krause on preserving the voices of the wilderness before they disappear forever.

Listeting to the great animal choir

Bernie Krause on preserving the voices of the wilderness before they disappear forever.

TEXT Jeremy Young PHOTO Ramin Rahimian

Despite the abundant flurry of chatter appearing throughout his vast recording archives of birds, mammals, insects, and other wild fauna, a typical morning in the life of Bernie Krause, now 78 years old, is actually quite . . . quiet. And if he can manage to keep the news from entering his house, either by radio or television, his day will also be tranquil. Krause wakes up early, starts the day off with a bout of yoga and stretching, then heads out to a nearby park for a two-to-three-mile (3-5 km) walk before breakfast.

“It gives me a chance to assess momentarily how I feel about the world and to get acquainted with its terms-du-jour,” Krause tells me, going on to explain how watching the news these days only serves to increase his blood pressure. The only remedy is to embrace the morning moment by moment, chatting with his wife Katherine and petting his cats, Barnacle and Seaweed, who apparently can’t take the news anymore either. And the only solace from society’s “blind need to embrace guarantees of certainty from leaders and institutions that have,” according to Krause, “remarkably small capacities for cultural, historical, scientific, or moral literacy,” can be found in the wild acoustic sanctuaries of the outdoors.

Yet for Krause, the outdoors are not for escaping the world, but deepening our understanding of our place within it.

Krause is a soundscape ecologist and naturalist, which means he records the sounds of natural environments and studies the sonic imprint of animal behaviour in a wild area, how that behaviour changes over time, and due to what circumstances. His archive contains over 5,000 hours of recorded habitats from every corner of the world, both terrestrial and marine. From which, over 15,000 individual voices—including everything from the elaborate love songs of Sumatran gibbons and thousands of variations of bird calls to the low crackling rumble of arctic glaciers moving underwater—can be heard and identified amongst the orchestras of the wild.

Yet while that volume of recorded data might not immediately seem enormous, quantitatively, what is truly impressive is that Krause was present in the field, headphones pressing against his ears, for every minute of activity on those tapes, an approach that has garnered both praise and backlash within the scientific community. For Krause, being there to administer the recordings and take contextual observations of the environment himself is an essential aspect of his research.

The detractors of this technique for studying biophonies (a term coined by Krause to describe the complete acoustic picture of a habitat) employ unmanned remote recorders spread out all over an area which capture short fragments of audio (30 seconds to 1 minute) throughout each hour of the day, opening and closing automatically like the shutter of a camera, accumulating a lot of data.

According to Krause, this “incoherent model . . . is a bit like trying to understand the magnificence of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony by taking 5-second snippets from every 30 seconds or so, and piecing it together.”

This fragmented approach does little to advance our understanding of how both climate change and industrialized noise pollution affect animal habitation in an area, and ignores the narratives of a place that can be uncovered in its biophony. He prefers attended recording—being present in the field to record complete event cycles.

In the late 1980s, Krause recorded an old-growth forest location called Lincoln Meadow in the Sierra Nevada Mountains to see how the area might be affected after logging.

“I obtained permission from a logging company in the process of introducing selective logging to their methodology, to record both before and after the operation. They had convinced local residents that their new method—taking out a tree here or there, rather than clear-cutting the whole stand—would have no environmental impact. In June 1988 I recorded my baseline data (I had recorded in the same spot several times over the entire decade, so I had a good idea of what the dynamic range of the biophony was over time), and one year later, after the operation, I returned and recorded again. The change in the biophony was palpable and the vitality of the natural soundscape has not returned in any of the 15 times I’ve visited and recorded since.”

When he returns from the field, Krause will analyze his recordings by listening, and comparing his notes against a spectrogram: a visual representation of the sound broken down by frequency and time. This allows him to pinpoint variations of the sounds produced by animals via isolated frequency clusters. In this particular case, the spectrogram produced an intriguing discovery.

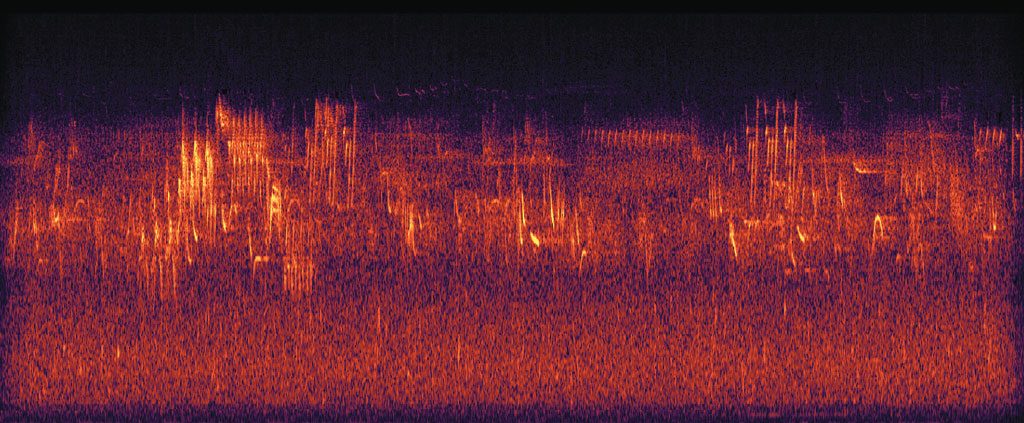

Here are the recordings from Lincoln Meadow back to back. Both recordings were taken in June, one year apart, and while to the naked eye, the landscape appeared untouched, the soundscapes tell a very different story. Above, the dawn chorus abounds with life; where the more intense colours represent loudness, we can see a flurry of activity in the upper-frequency registers suggesting the melodic tonal movement of birdsong and the rhythmic jitters of insects chirping. Each cluster of yellow represents a voice moving through time, against a healthy backdrop of white noise provided by a flowing stream and wind passing through the leaves. And below, this vocal activity has all but vanished, along with the trees that made up these animals’ homes.

As the isolated light clusters of the spectrogram indicate, animals cohabiting the same environment alongside many other species are able to adapt their callings to find their own personal acoustic pocket within the frequency and timbral spectrum. Over time, animals tune their calls so that they are able “to find signal-free bandwidth for their voices with-

in the animal choir,” explains Krause.

In his book, The Great Animal Orchestra, Krause suggests that over the course of thousands of years, this natural model for tonal and timbral interaction has helped shape the architecture for the modern symphonic orchestra. His theory is that humans learned how to build instruments to produce the same diversity of timbres found in the wild, and how to organize musical relationships in composition, guided by that very principle, that every voice needs its own auditory space.

And he should know. Krause’s interest in music goes much deeper than listening to birdsong. In fact, his career trajectory reads almost like a Forrest Gump–style cross-country meandering of influence across some of the most important urban movements in art and music in the 20th century. Whether by chance, or pursuit, somehow Krause was present and influentially active in watershed culturally historic moments, such as recording sessions for Motown Records in the 1950s, the folk explosion of the early 1960s when he occupied Pete Seeger’s post in The Weavers, the flourishing of the electronic and tape-music avant-garde around composers like Karlheinz Stockhausen and Pauline Oliveros, both of whom lectured at Mills College in the Bay Area where he studied, and Krause even contributed to the introduction of the synthesizer into hit pop and rock records (having performed in studio sessions with The Doors, Stevie Wonder, George Harrison, and Van Morrison, to name a few). In the early 1970s, with his late collaborator Paul Beaver, he created what many consider to be a hallmark record in the birth of ambient new-age music, and then went on to record diegetic soundscapes in seminal feature films such as Apocalypse Now, Rosemary’s Baby, and The Conversation.

For all the symphonic abundance of animal song appearing in his recordings, what he has in fact captured is the sorrowful sound of radical change moving toward silence—shifts in the biophony due in part to global warming, habitat destruction, and human transformation brought about by development, mining, logging, drilling, and anthropophony (human noise).

His recordings capture powerful expressions of change and what it portends in localized wild habitats. When change happens in a landscape that resident animals have evolved to understand from an auditory perspective, they may never be able to readapt. Just like Lincoln Meadow, Krause explained to me that “when a habitat is under stress from various kinds of resource extraction, no matter how seemingly inconsequential to the eye, the biophony will always and immediately reveal its true condition.”

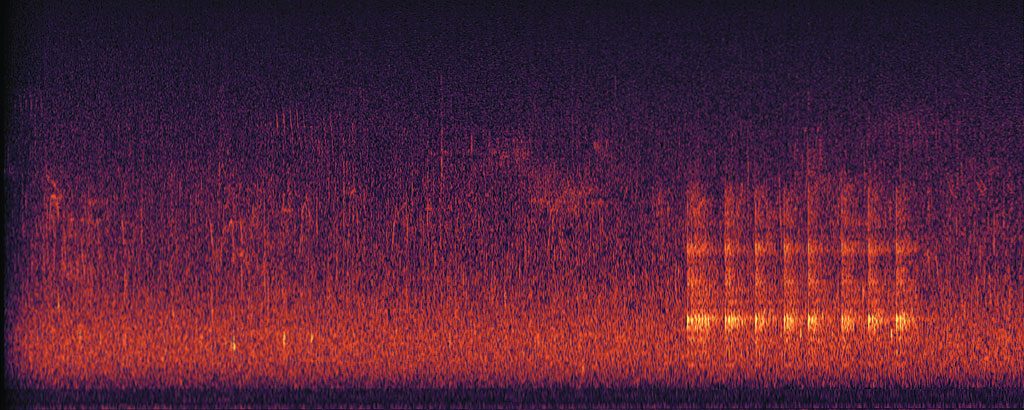

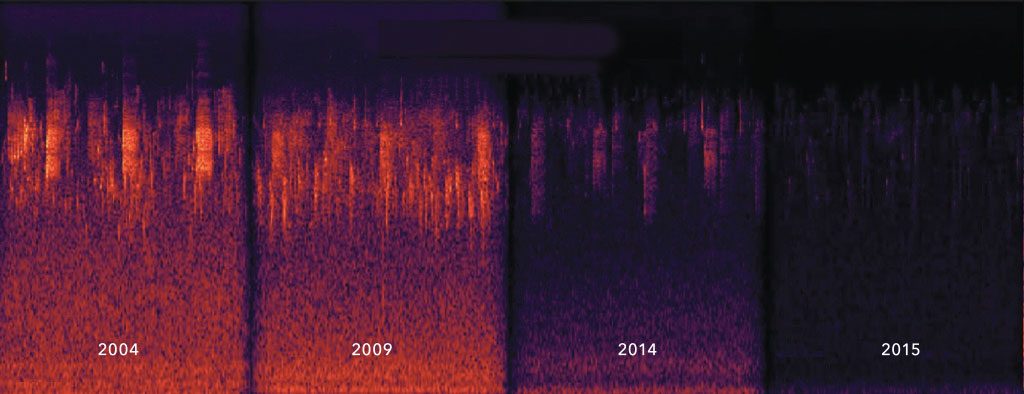

One spot Krause returns to frequently is Sugarloaf Ridge State Park, only a 20-minute drive from his house in Northern California. The recordings made there provide a recent history of climate change expressed through the narratives of the biophony collected over the past two decades.

That’s not a doctored image. The chart’s increasingly darkened space, representing the great quieting of the local biophony, was, according to Krause, almost exclusively caused by the long-standing Californian drought, the most significant lack of rainfall in the area in over 1,200 years. In this spectrogram image, you can see not only a drop in the indications of bird species (marked by rhythmic clusters in the upper frequency ranges), but the disappearance of the low-frequency signature of rushing water. Along with the birds, the streams have gone away as well.

The unprecedented changes accelerated by the plague of global warming are silencing the great chorus of wildlife everywhere. As the earth’s polar ice caps melt and raise the average temperatures of the oceans, even by as little as 0.5°C (1 °F), we’re witnessing the rapid global extinction of coral reefs. And you can hear this too. Hydrophonic recordings of marine environments reveal shifts in both the density (total number of all vocal organisms) and diversity (total number of distinct species) of sound-producing organisms.

And it isn’t just the radical environmental changes of global warming and deforestation that affect animal behaviour and populations in an area. Data suggest that the extended introduction of any intrusive human-generated noise (anthropophony) into an ecosystem, even from miles away—such as jet overflight or audible construction—has a direct correlation with the expression of its biophony. We take up a lot of space. And our sonic footprint takes up even more of it.

As I took the time to listen through some excerpts of natural soundscapes on his website, from the birds and frogs of equatorial rainforests to the humpback whales of the Pacific Ocean, I became more immediately aware of the animals cohabiting this planet with us.

Krause recounts a memorable trip to the Amazon jungle with a colleague. Several kilometres away from camp, with no light but that of their flashlights, and hoping to capture the evening tapestry of rainforest biophony, they set up their mics and walked 30 feet away so as not to influence the recordings. Along the trail they encountered the musky feline odour of a nearby jaguar, following them at a distance, defensively marking its territory. They never saw the animal. Suddenly, with his headphones turned up, Krause could hear the low growls of the jaguar breathing, its stomach gurgling, in full detail. The cat was no more than an arm’s length away from the microphone, but in an instant, it disappeared into the darkness, leaving the soundscape to the frogs.

To listen to wildlife up close reminds us that we may not always be able to see the damage we leave behind, the ways in which we intrude, especially when the residents of a habitat are forced to retreat. But that is no reason not to account for them. For the wildlife with whom we share this continent, the biophony is their voice and it begs to be heard.

***

Editor’s Note

I interviewed Bernie Krause for BESIDE Magazine’s second issue exactly a year ago, and it has become dramatically evident that a lot has changed since we last spoke. In preparing for this repost, we contacted Krause to request his permission to run this piece and his response floored us, sending uncontrollable tears down my face almost immediately.

Bernie & Kat Krause’s house — and everything contained within it, as well as nearly every blade of grass growing on the land around it — was burned to the ground by the Northern Californian wildfires in October. Both he and his wife barely escaped with their lives as flames engulfed their entire property propelled by wind gusts up to 130 Kph at 2:30AM. Lost forever, gone in mere minutes: an entire life’s archive of music, writing, field recordings, research, and photographs, as well as the original instruments and equipment used to bring this work to life over the span of nearly 50 years (including an early wire recorder, not to mention rare synthesizers and guitars), and, perhaps most sadly, his two cats, Barnacle and Seaweed.

There is no upside to Krause’s situation. In his email two months after the incident, he mentions that procuring bedding, towels, and underwear, still remained a priority — and for anyone anywhere to lose everything they own, let alone someone with one of the largest personal archives of nature recordings on the planet, this is a life-changing, category 5 disaster. And yet, inspiring glimmers of hope shine impossibly bright through some of Krause’s most casual admissions. Although they miss their books, their cats, and the view of the Sonoma Valley property that they enjoyed at the start of every day, he writes, “I visited our burned out place yesterday and although the site has been utterly transformed… there’s a carpet of green shoots where grasses are beginning to sprout. Some of the trees, badly burned in the fire, are even showing tiny signs of life. So we’re being told by the life forces around us to just cool it and things will eventually come back in some yet-to-be-determined new form.”

Although this outlook is no doubt touching, how much hope we can hold out for those baby grass sprouts remains grim. The menacing jaws of climate change have shown only an insatiable hunger to devour more — such was certainly the case this autumn up and down the Pacific coast. Please read on to find out just how vital this makes the continuing proliferation of Krause’s work, which details the human-influenced displacement of animals from their habitats, and provides auditory evidence of the unseeable changes we’ve made to our landscape. Thank you Bernie, for sharing generously your work as well as your story with us.

– Jeremy Young