New Narratives

“I fear returning to the very places I love.”

Professional snowboarder, filmmaker, and activist Tamo Campos reflects on recent life-changing events that have both awakened his deepest fears and brought him new perspectives.

It’s fall, the time of year when my daydreams are filled with the excitement of the first snowfall, when I patiently await the feeling of breathing in fresh, crisp mountain air. I crave the familiar sound of a splitboard breaking trail through sparkling snow, cutting through that calm silence that only winter knows. But this fall, my excitement is clouded with fear and anxiety about the winter to come.

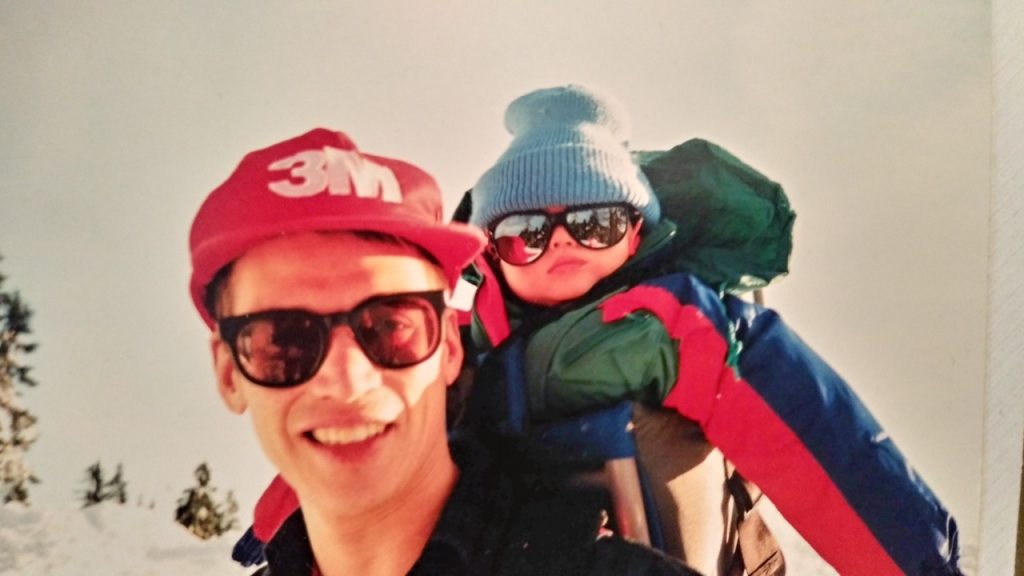

For extreme sports athletes like me, can the mountains be a place for healing, even though they’re the source of my wounds? “I don’t need a church. I just need the mountains and my hope is that heaven is an endless powder run.” I’ll always remember these words from my dad. He wasn’t religious, he just really loved the mountains. I was only 11 days old when he first took me into the backcountry—stuffed into his backpack. He and my mom took me skiing as if it was nothing out of the ordinary. By the time I had made my first trip around the sun, I was already familiar with the backpacks, tents, and ski clothes my parents would haul, along with me, into various mountain ranges for overnight expeditions and trips.

My family was crazy. Thanks to them, there was no question that I’d fall in love with the adrenaline-pumping nature of extreme backcountry skiing and snowboarding at a young age. 28 years later, I’m still chasing an endless deep-snow run. But the mountains do bite back: broken bones in my feet and wrists, shoulders dislocated, ribs pushed out of place—every one of these season-ending injuries only made me more excited for the ski season to come. But this past winter’s injury was different. This one might be permanent. While splitboarding for a documentary film project called, The Radicals, I fell into a windlip on the Bridge River glacier. I literally fell straight into it, smashing my face. My adrenaline was pumping so hard that I was able to immediately get myself out, but only days later, the symptoms of a serious head injury started to take hold. My eye was swollen completely shut and I had to fight to stay awake.

The clinic’s diagnosis was a cracked orbital bone in my sinus passage—and a major concussion. But I don’t even remember seeing a doctor. I don’t remember a lot of things. My partner had broken down in tears when I’d come home. I had been slurring my words and I must have seemed drunk. The way I had hit my head affected the circadian rhythms in my brain. These naturally produce melatonin in order to help regulate sleep patterns. As the weeks went by, I could count my hours of sleep on one hand. Soon I felt the slow slide into madness. I had never struggled with anger in my life, but now my temper would boil up over nothing. I would sit on the couch, fists clenched, feeling insanely frustrated, without knowing what I was fuming about. Tears would stream down my face as I wondered if this was the new normal. To immobilize your leg when it’s broken is one thing; to immobilize your brain is next to impossible. In fact, one of the hardest parts of dealing with my injury has been the mental game of wondering if I’ll ever get my personality, my memory, and my mind back. The injury took place in the heart of winter when the snow still blanketed the ground. By the time summer came around, I was still experiencing ups and downs, but eventually I found emotional stability. The personality I had come to recognize as my own came back, anger subsided. I still feel slightly awkward in my body—one bad night’s sleep can set off waves of symptoms—but the route to recovery is underway. The only thing I’ve yet to conquer is a new feeling for me entirely: fear. Adrenaline sports take full mental commitment, and require a keen, balanced relationship with risk and fear. What used to be a requisite emotion as I would gear up to do what I loved the most is now pervasive, and it clouds even the thought of doing those things again.

The mountains can dish it out, but they are also a place of healing. During one of the hardest times of my life, I found strength in these mountains. A few years back, my dad passed away suddenly on an adventure of his own. He had never motorcycled before and in our family’s patented style, decided to do his first trip from Tierra Del Fuego in Patagonia to Vancouver—a small trip of 18,000 km. Tragically he was killed in a hit and run in Guatemala, hundreds of miles away from any family or friends. Like my crash up the Bridge River, it was a shock to everybody. The unexpected nature of these events left so many unanswered questions. Heavy clouds hung over me like a forest thick with smoke, preventing my own thoughts from getting out. During this time, I found solace in the mountains. The wilderness had a way of clearing my mind—of bringing me back into my body. Being back on skis brought me into the present moment. It brought me spiritual answers. Immediately after his death, I had worried that my dad’s spirit was stuck in Guatemala. But when I gained enough mental strength to begin touring in the mountains again, it became clear that we were hiking together. I felt his presence, heard his skis swooshing behind mine, and I knew that he’d made it home. Or as he’d say, his spirit was on that endless, heavenly powder run.

You never fully heal from either. Both leave you vulnerable and changed, but with time they can bring you new perspectives about yourself and the world around you. I will eventually overcome my fear of the mountains. And I can both blame and thank the mountains for this. They stand as a humbling reminder of the great strength within us all, and they are a true sanctuary for those who can see them that way.

—