BESIDE X NOKIAN TYRES

The Finnish Lifestyle

How Finnish entrepreneurs are reimagining the Nordic lifestyle.

The Nordic landscape is home to both great adversity and near-constant change.

In summer and fall, Finns hike deep into Lapland, picking crimson berries they’ll later use in hot, flaky pies and unearthing damp mushrooms clustered around alder trunks. But come winter, snow flattens the countryside and muffles most of the natural world into silence. Reindeer hooves penetrate the icy crust shielding delicate carpets of lichen, and Nordic ski tracks artfully cross the frozen surface as if lighter than a feather. Finland has twice been named the happiest country in the world, and many attribute this nationwide contentment to a lifestyle deeply rooted in nature. “Most people have access to the forest, even if you live in the city,” says Aino Paavola, who lives in the mini metropolis of Tampere, where she works for Nokian Tyres. The woods are less than 1,000 feet from her home.

Everyman’s Right is a rule which governs Finnish people’s access to wild places. The law, established in the 1990s, dictates that everyone has the right to roam: to hike, to ski, to bike, to bathe in nature and its beauty. Property rights, on the other hand, hold no value here. The Finnish upbringing, therefore, encourages a close connection with the natural world—Finns are thus quite well-equipped to handle the fickle temperaments of this northern landscape and its weather. More than a third of Finland lies above the Arctic Circle, so from November to January this region endures never- ending darkness. To endure, Finns have implemented the idea of “sisu”—tenacity and stoic determination in challenging times—to not merely survive but thrive in some of the coldest, darkest, harshest winters on earth and come out on the other side stronger than ever.

But times are changing. The North is warming and the Arctic’s fragile permafrost is thawing and young Finns are spending more time indoors than ever before. The reindeer have also begun to disappear. But visionary entrepreneurs, driven by a passion for sustainability and environmental stewardship, are repurposing and reinventing Finnish traditions, as well as using stalwart determination, to overcome the challenges of the land and preserve the Nordic way of life so that it can be enjoyed year-round by citizens and visitors alike, and safeguarded for future generations.

Nokian Tyres

Bringing safety and security to the North.

_____________

The road to “White Hell” is paved with good intentions—but unfortunately covered in a thick layer of ice. Located in Ivalo, 155 miles [250 km] north of the Arctic Circle, this is the world’s largest winter tire testing facility, owned and operated by Finnish company Nokian Tyres. What happens here ensures the safety of millions of people who must travel through harsh conditions—whether for work or pleasure.

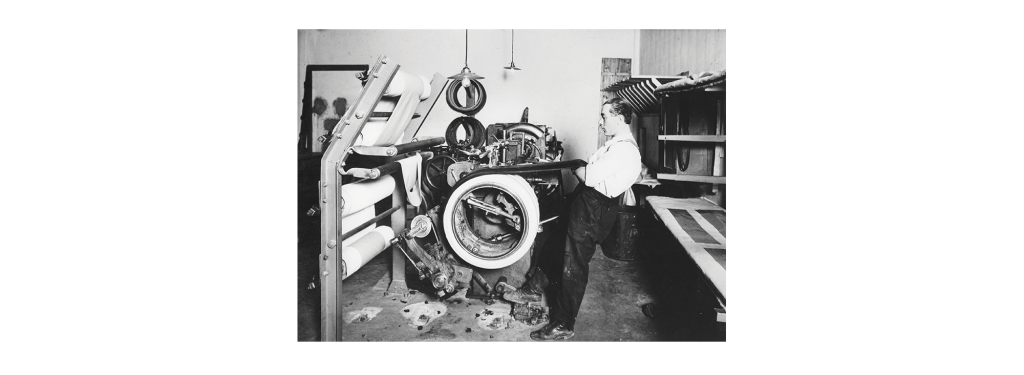

Nokian Tyres invented the first winter tire, to suit tough Nordic conditions, made of rubber with special toothy tread patterns for added grip in snow, ice, and mud, in 1934. Nearly 50 years later, Nokian Tyres opened the Ivalo Testing Centre—nicknamed “White Hell,” a spin on the European Nürburgring racetrack sometimes known as “Green Hell”—to carry out trials of their award-winning product under extreme environmental conditions. Every year, this corner of Lapland experiences more than 200 days with temperatures below freezing. “Finland is on the exact same latitude as Alaska,” says Antti-Jussi Tähtinen, global vice-president of marketing and communications at Nokian Tyres. “When the ground freezes, the roads freeze. That requires a different kind of tread than the all-season tires people use in the rest of the world.”

“What makes a good winter tire is that it’s predictable,” explains Tähtinen. Drivers need to know that their car can handle tight corners and high speeds on less-than-ideal roads. In Nordic countries, he says, everyone is used to losing grip in snow and ice conditions, so testing to create the best possible winter tire is key.

Paavola, a communications specialist at Nokian Tyres, often depends on these tires to get her to the woods to pick berries and mushrooms. “It’s totally normal to live in the middle of the forest with kilometres and kilometres between you and your neighbour. So of course you will need to have a car.”

Nokian Tyres isn’t just the northernmost manufacturer of tires, they’re also one of the most sustainable—and they encourage entrepreneurs to find ways to preserve Finnish traditions while also building a more sustainable future for the country.

“Finns, perhaps, have some Slavic melancholy, but we are still quite sensible people,” jokes Paavola, before explaining that tires with low rolling resistance use less fuel but allow cars to go farther, which is good for nature. “It’s sensible, like buying second-hand or having a smaller house.”

The Nokian Tyres Hakkapeliitta winter tire already uses renewable raw materials, including canola and pine oils that improve the tire’s grip on ice, ultimately reducing fuel consumption and CO2 emissions.

Bio-based tires, however, are just one of the several sustainable strategies used by Nokian Tyres—they’re testing tire designs for self-driving electric cars and powering their warehouses with solar panels as well. “Not too many people live here in this cold climate, and in return we get clean air and clean water,” says Tähtinen. “We must protect it.”

At 68 degrees north, winter tires aren’t a luxury—they’re a necessity. “In wintertime, it can be dangerous to drive,” says Tähtinen. “But you have to get your kids to school. You have to go to work. Life has to go on during the winter. And we have to make sure people get there safe and sound.”

White Hell, therefore, is anything but. At night, hues of pink, indigo, and violet light more than 30 test tracks spanning an area larger than 1,000 football fields. The sun won’t crest over the horizon here until February. In the winter season, professional drivers will test more than 20,000 tires on snowy, slushy, and frozen tracks, continuing on into May when varying temperatures create tricky freeze-thaw conditions that can confound everyday drivers. In Lapland, temperatures swing as wildly as 40 degrees in a single day, so if a tire works here, it’ll work anywhere.

Ultima Restaurant

Using tech and tradition to design a local, sustainable cuisine.

_____________

In the centre of Helsinki exists one of the most unusual dining experiences in all of Europe. Crickets chirp in balloon-shaped pendants. Mushrooms unfurl in leftover coffee grounds. Potatoes lie rooted in aeroponic tubes. And algae flourish in a gurgling hydroponic system. Here at Ultima Restaurant, the farm-to-table concept has been invented anew—the farm nearly is the table.

Chefs Henri Alén and Tommi Tuominen describe Ultima, which opened its doors in 2018, as “hyperlocal,” driven by sustainability, tradition, and a distinctly Nordic palate. Deeply ingrained in their ethos is the concept of the circular economy and the fluid integration of cities and farms.

Finnish food is renowned for its edginess compared to the rest of Scandinavia, moving well beyond meatballs. “People have moved here from Sweden and from Russia—everywhere,” says Alén. “It is important to preserve our Finnish tastes and traditions. You can’t build a future if you can’t define the past.”

Ninety per cent of the restaurant’s in- gredients have Finnish origins, but they are used to create both Nordic and internationally inspired meals—from elk tartare to smoked Baltic herring to rabbit liver. Diners can even munch on crickets; Alén fashions an edible paper from the crickets that can be consumed like a snack.

But the challenge of cooking with ingredients grown only in Finland can be monumental. The Arctic’s short growing season means that technological innovation is needed to ensure that both food and food preservation is sustainable. Without such innovation, Finland will become overly reliant on imports that slowly chip away at Nordic culture.

Therefore, the ability to grow fresh food on Ultima’s premises year-round is a revolutionary advancement in a city where temperatures regularly plunge below -20 °C [-4 °F]. It’s also one that Alén hopes can be replicated around the world.

“We are a Nordic region and it’s a harsh life. If we can do this here, we can do it anywhere.”

—Henri Alén

Löyly Sauna

Building a sense of community.

_____________

Is there anything more Finnish than a public sauna?

Jasper Pääkkönen doesn’t think so. “It’s the single thing that defines Finns and the only word from the Finnish language to travel so pervasively to other languages,” says the Helsinki entrepreneur, stretching out the vowels of sauna into a near-moan.

In North America, saunas are treated as a rare indulgence—a cozy respite after a cold day out skiing or snowshoeing. But in Finland, sauna is simply a way of life. Traditionally, the sauna, a small room heated with wood or hot stones, was used to warm the rest of the home. It was also the place of birth and death in early times—Pääkkönen’s own grandmother was born in a sauna.

With a population of 5.5 million, Finland boasts an astounding 3.3 million saunas—that’s 1.6 saunas for every single family. “It’s more common to own a sauna than a car,” says Pääkkönen, an avid fly fisherman and environmental activist who works as an actor on the side (he appeared in Spike Lee’s film BlacKkKlansman in 2018).

Public saunas used to be much more common in Finland and served as a place of bonding and socializing. “Helsinki alone once had over 100 public saunas,” explains Pääkkönen. With the proliferation of apartment living and privatization of space, the role of saunas in public life declined.

Enter Löyly. In 2016 this sauna—a feat of Scandinavian design—opened on the Helsinki waterfront. Two large saunas—one wood-burning and the other a traditional smoke sauna—border the edge of the Baltic Sea, providing visitors with the unique ex- perience of ice-floating in the open ocean. Hundreds visit these steamy wooden rooms every day, sharing space and stories. “The cultural need and attachment for saunas has never gone away,” says Pääkkönen, one of the cofounders of Löyly—the name translates to the steam that radiates from the rocks in the sauna. In Old Finnish, löyly also means “spirit” or “life.”

Pääkkönen hopes that places like Löyly can keep Nordic culture alive, not only for Finland’s inhabitants but for visitors, too. “There is nothing else a visitor to Finland could experience that is more authentic than doing a sauna.”

⁂

As the Nordic region changes, Finnish people are adapting and innovating in unparalleled ways. From sustainable, winter- ready tires and farm-restaurant fusion to saunas that serve as social clubs, Finland is meeting the challenges of Nordic life head-on. In doing so, the country is inspiring the rest of the world.

Life in the ever-changing Arctic has perhaps never been this difficult. The region is warming at twice the rate of the rest of the world; the weather is becoming increasingly unpredictable, and so is the future. But Finns are drawing from their past and passing those lessons down to future generations through simple and sustainable food, social cohesiveness and safety, and security. They have deeply defined their way of life, even against the odds, implementing the Finnish idea of sisu and sustainably innovating to safeguard their traditions and culture for years to come. ■