Village

Tim and Hannah’s ark

How a young couple beat the flood of modern chaos and built a tiny salvation.

TEXT Kathryn Borel Jr.

PHOTOS June Bhongjan

Artist Hannah Fuller and pro snowboarder Tim Eddy had been building their secluded, Swiss Family Robinson–style microcabin with their bare hands for two months. Suddenly, on week six, all their utopian plans to live sustainably were halted. By a toilet.

It was the summer of 2012, an unending streak of classic NorCal weather: blue skies, sunny, 24 ˚C (75 ˚F). Their project to build a 100 per cent off-the-grid, 196-square-foot home was going smoothly, in spite of Eddy having no experience with construction and Fuller’s knowledge of architecture being limited to the sailboats her father Rob manufactured. Hannah’s parents had shipped in a pallet of custom tools from Maine and flown out to oversee the experiment. Morale was excellent, largely hinging on Eddy and Fuller’s boundless pink-cheeked positivity and near-symphonic capacity for teamwork. The frame was up, complete with doors and windows. The next project was to lay the shingles. Every night at 8 p.m., covered in a film of sawdust and sweat, after a dinner of meats and vegetables cooked on the campfire, they’d all pass out in their tents, only to wake up at sunrise and do it all over again.

Then, in mid-September, about two weeks before the exterior of the house was complete, Fuller and Eddy got red-tagged by the county. Officials had deemed the construction in violation of the law.

“One of our neighbours must have heard tools and called the county officers to investigate what we were building. Our plan was to build what qualified as an accessory structure, which is under 200 feet. But we were told that you need a permanent structure if you’re to have an accessory structure,” Eddy explains.

The officer admitted the law wasn’t written well, and clarified that what differentiated their cabin from a county-condoned permanent residence was a septic line and a functional, flushing toilet. Eddy and Fuller were forced to stop building.

Fuller was heartbroken. “I was so upset with the way the world works. Here we were, doing a project that was about positivity, with zero footprint. On land we owned legally. But that doesn’t matter. You still have to pay The Man.” Galled and mystified, they left the county office and checked into a motel. The two took their first hot showers in weeks.

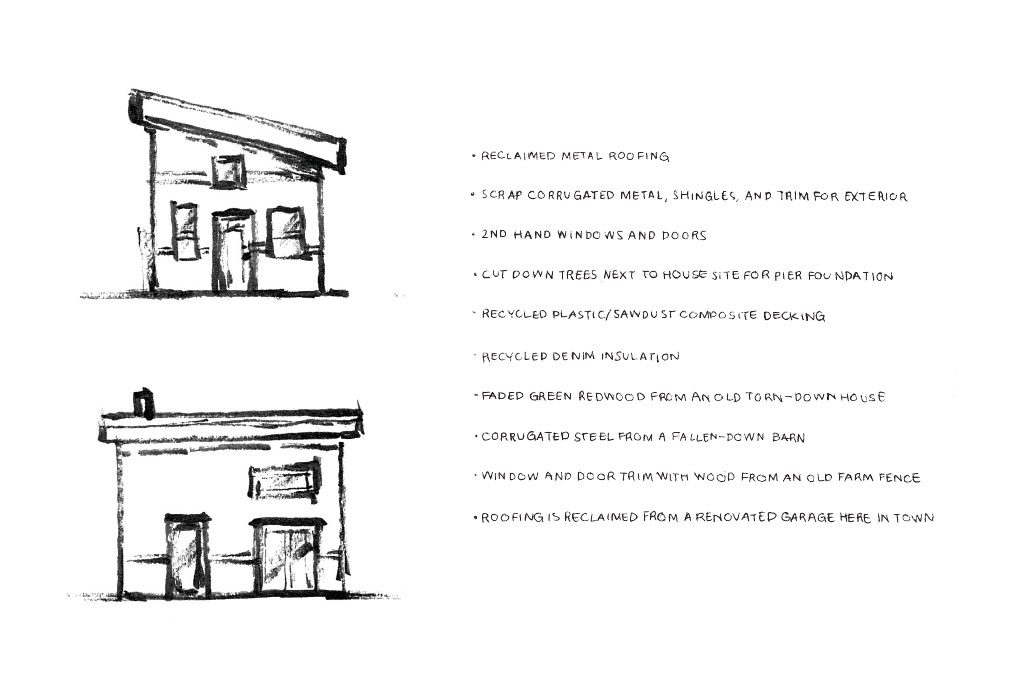

“We just had to get creative,” Fuller says. But that was something to which they were accustomed, as every step of the cabin’s development came from a place of rigorous ingenuity. Fuller and Eddy used felled trees from around the building site as the post foundation. The doors and windows were reclaimed. They—legally—snatched surplus flooring and interior siding from a local job site, and hauled old roofing from a torn-down garage in Tahoe. Down to the tiniest detail, the couple integrated only recycled and low-impact materials into their design. Even the weatherproofing material they used for untreated wood was crafted from tomato cans Fuller saved from her job at a pizza joint. So working around this new set of challenges simply required another bit of ducking and weaving.

But before all this—before the cabin blueprints and the big chunk of boat tools—Eddy and Fuller were just a cool young couple living in a cool normal condo in Lake Tahoe. They had a 36-inch TV, a Vitamix blender, and, of course, a sparkling modern toilet. Fuller worked early shifts making pizza dough and pastries at various restaurants around town so she could snowboard in the afternoons with Eddy. Eddy would take off for weeks at a time to ride in Japan, South America, British Columbia. His life as a pro athlete was a whirl of plane rides and catalogue shoots. Yet something wasn’t quite right.

“When I wasn’t snowboarding, I’d go back to the condo and feel confused. Being out in the mountains as often as we are, we have that connection to the environment. The way we were living wasn’t correlating with our values.”

Then Eddy had an accident. He was shooting photos in the backcountry and slipped and cracked his tailbone on a tree stump. Unable to sit or stand without going into convulsions of pain, he stayed cooped up inside the couple’s condo, lying on his stomach. From that perspective, he began to see everything through a filter of excess and waste. So did Hannah. “We’d look at brush fall and think, ‘That’s firewood,’” says Fuller. “Or I’d try to sneak little piles of compost here and there. We’d done a lot of backpacking so we understood how a composting toilet worked. And we decided that we owed it to ourselves to use that knowledge.”

When Eddy’s backside healed, he got right off it, put the condo on the market, found a 20-acre plot of land, and two weeks after the sale closed, the couple was bunking down in a tent on a bunch of dirt, 15 miles (24 km) outside of Tahoe. They read a few books on tiny houses, asked Fuller’s dad a million logistical questions, and got to work. Every day in this new pine-scented wonderland, among the old-growth branches and fallen needles, a great internal reevaluation was happening. They became freer, more confident, less burdened by the constructs and expectations they’d been swallowing during their early 1920s. “It was an epic transformation,” says Eddy.

The build kicked into high gear, even though technically the county had barred them from continuing the project. Eddy and Fuller put in insulation made of recycled denim, finished out the kitchen and bathroom, and installed the crown jewel of the cabin, the wood stove. Bolstered by their quick progress, they studied the law and found a way to justify the construction of a huge concrete skate bowl.

“It was a bold move, but it’s just an articulated slab. I knew they couldn’t bust us on that. We started taking full advantage of the slow-moving bureaucracy,” Eddy says.

“We know our stuff so well now, so whenever they bug us Tim will just rattle off a bunch of codes,” says Fuller. “We’re such a headache for them.”

Finally, they came up with a way to solve the toilet problem. The answer was not an actual toilet, but an intention to install one. The couple bought a septic permit for $600, which appeased the county into believing they had an intention to build what the law regards as a permanent residence.

Over the last five years, through the steep learning curve they managed to dominate, and the sustainable builders they’ve met and befriended, their plans have, in fact, extended further than the little cabin. The plan is to build a larger cabin that meets the county requirements of a permanent residence.

“We are going into the project with sustainability, simplicity, and functionality all working together, taking bits of knowledge from permaculture where all the elements serve more than one function and provide supporting roles to each other. We have also taken the time to observe and interact with our property in order to familiarize ourselves with it. Our new site will have a strong south-facing side to power our solar panels, westerly views, proper soil for the septic, and shade from beautiful ponderosa pines.”

There will even be a real toilet. “It will be the smallest standardized system we can manage,” Eddy says. The couple then cracks up with the delight of two people who haven’t just gotten away with something, but have gotten away from everything that isn’t essential to who they are. ■

—

To read more . . .

This article was initially published in Issue 02 of BESIDE Magazine.

Magazine 02