New Narratives

A Fugitive in Montana

Escaping a wilderness rehab and hitchhiking across a state, Simon fought hard against letting nature change him.

Text—Simon Hudson

Illustrations—Mélanie Masclé

I did not go willingly. At 3 a.m. I got woken up by my parents struggling with the words to tell me I was going away. They had signed custody over to two ex-Marine types who were also in my room; they would be taking me on a plane to the woods of Montana.

I knew my parents had been planning to send me to some kind of rehab soon, but I didn’t expect it to happen before the end of the school year. They had gotten a glimpse of the trouble I was getting into (weekend disappearances, a discovered shopping list of drugs, suspension from school for fighting, manipulative emotional breakdowns) and decided that overreacting was better than underreacting. The escorts were an addition because they rightly deemed me a flight risk.

I lived up to their expectations when I made my first escape attempt at the Seattle Airport check-in counter. It was 4 a.m. and the airport check-in area was empty except for the stanchions and connecting straps set up to corral the travellers who would be arriving in just a couple of hours.

As I stood behind my escorts at the ticket counter, I had a feeling that their attention had momentarily drifted from me to the agent. I saw my window and leapt for it.

And I managed to get some good distance away from my kidnappers, too, until I ran into a slow-opening automatic sliding door. I turned around to look for another route and discovered that running away from people in an airport post-9/11 led to several government agencies being alerted. I tried to juke around them but was tackled to the ground and put in cuffs. After explaining to Homeland Security why they were transporting this minor, my escorts had me on my flight headed to my new summer camp without any further hiccups.

Brat camp

When I arrived in Montana, I had to admit that, despite my protests, my parents had made a good choice of where to send me. I have always loved the outdoors, whether camping with my dad, school trips to go kayaking in Alaska, or hiking in Wyoming. But I couldn’t handle losing my self-determination; I was outraged.

Three Rivers Montana was a program for troubled and/or bratty teens of all stripes based on the principle that “Nature cannot be manipulated, but instead demands good choices.”

After a blindfolded drive to the camp to meet with the group, I was informed of what the general schedule of my life would be for the foreseeable future (they insisted the duration of my stay was entirely up to me). Each morning we would wake up, warm up with calisthenics, drink 1000 ml of water, eat breakfast, load up our external frame packs, and then hike. They would not tell us how long we would hike, but the average was seven hours and we weren’t allowed to talk. Much of the hiking was off-trail, keeping us from getting a sense of direction or running into other hikers, not that there were many in the Gallatin Mountain Range of southwestern Montana.

Arriving at our camp for the night at the end of each trek, we would go into our survival work. Hooches—thick tarps draped over a line and the corners tied down with cord—were our main shelters: one “mama hooch” for the cooking area and one personal-sized for each of our sleeping spots. We then went on to dig our latrine and firepit, carving them out so they could be easily refilled and resodded the following morning.

We each had our own food for the week: plain, dehydrated ingredients went a long way with a hungry imagination stimulated by the silent treks. The catch was that hot meals required building our own fires with wooden bow drills. If you couldn’t achieve the small cherry of a coal with a bow drill and build that into a fire, well, your dining options were significantly limited. Imagine being drenched in sweat, arms cramping out, just to see a trickle of smoke, and in the end your dinner is cold powdered mashed potatoes.

At the end of each week, we would remain in one spot for two nights to resupply. A new set of counsellors would rotate in, bringing with them the new supply of food and letters from our parents. We used the downtime to meet with a psychologist and complete coursework on topics ranging from navigation, constellations, and botany to anger management and family conflict resolution.

I joined the group on a resupply day, and so I had a chance to send a first letter to my parents. I listed everything wrong with their decision; I threatened to disappear if they didn’t bring me back.

For dramatic effect, I signed it in blood from a cut I got when sawing a sapling for my bow drill (I didn’t know these letters were actually faxed in black and white).

(Here’s a video of me reading the letter at the event Grownups Read Things They Wrote as Kids. Rereading the letters, the word “arrogant” comes to mind.)

My botched escape attempt from the airport had put the counsellors on alert, so I decided I should lie low and give my parents a chance to change their minds and bring me home. I was also keen to learn how to make fire with only sticks and twine, which I thought would be handy if and when I needed to escape the backcountry.

Hitchhiking through Montana

Without meaning to, I changed in that first week while waiting for my parents’ letter. Daily treks in silence are an effective way to get anyone to reflect on their lives and consider what’s really important. My mental fog lifted, and I saw clearly that the substances I had been using were blurring my days, weeks, and even hours into one chaotic haze. I knew then that while they may have “opened my mind” to new ways of seeing the world, they had long darkened my perspective by making me dysfunctional and anti-social.

After learning to make fire with sticks and having my revelation about drugs, I decided I had gotten all I needed out of this camp and that it was time to go. When I received a letter from my parents rebuffing my proposal to bring me home, I made my second escape attempt. This time I got out.

I saw my opportunity early the next morning while the counsellors were a hundred yards away at the campfire. I was ready with a couple of apples and full water bottles. I didn’t wait to second-guess it, I just went, leaving behind a letter that said, “If I do die on my path to freedom, it was completely worth it because I have the power to make a decision for myself and I am in control.”

(I also wrote a list of confessions I carried with me in case I didn’t make it. Here’s the recording from another GRTTWK event of the letter I left behind at 29:06)

My plan was to hitchhike to Missoula, where my dad had grown up and still had close friends living there. I had gotten a glimpse of a map from one of the counsellors and saw that Missoula was about 300 miles [483 km] away. I ran about 12 miles [19 km] before I made it to the highway, where I pulled out a piece of my sleeping pad into which I had carved “MISSOULA”.

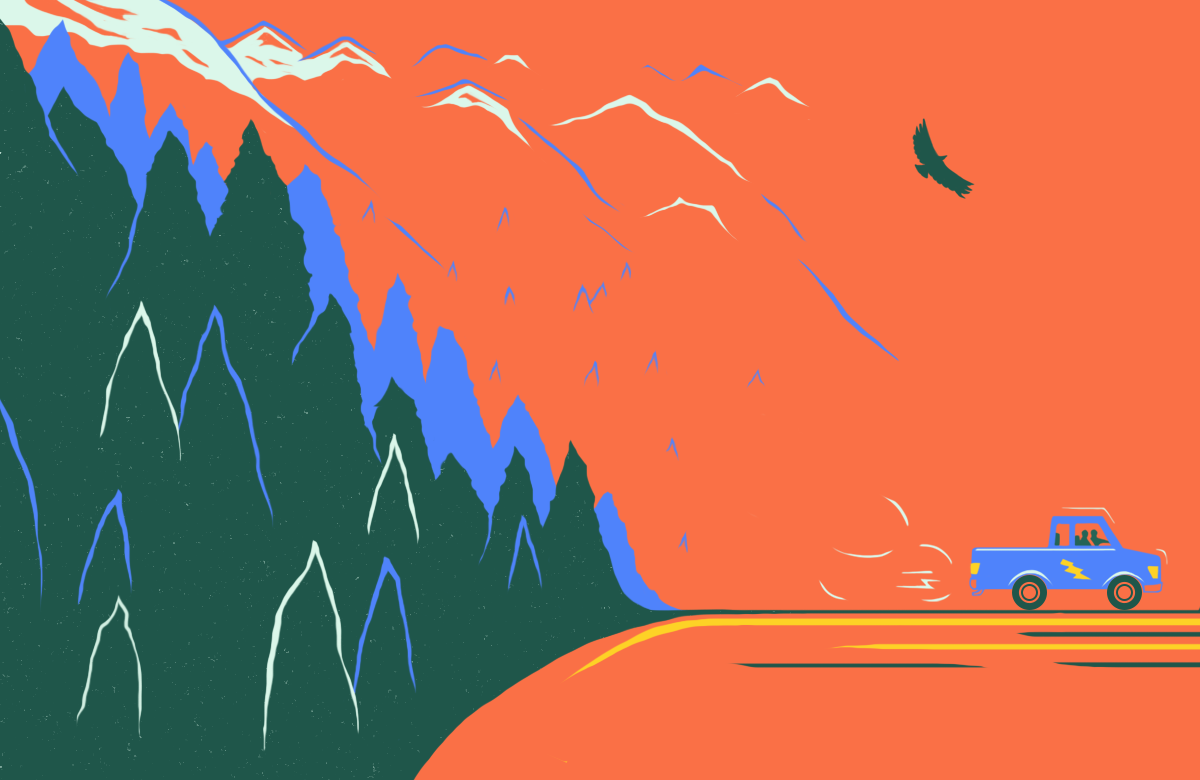

It took me only two rides to get all the way there. The first guy freaked me out at first; he looked like a cop because of a large antenna on his pickup, which turned out to be a car phone. He didn’t talk much and was skeptical of my story about how my camping group had agreed to not report in if we got separated from each other, but didn’t push the issue. He gave me a Gatorade and let me call friends back in Seattle.

He didn’t point out that the voicemails I left for my friends seemed to conflict with the story I had told him—he just offered me beef jerky and told me how he bowhunted grizzlies, as well as that his daughter’s safety was the most important thing in the world to him.

Along the way, he dropped me at a gas station while he ran some errands in town. Going into the gas station was the first time I realized how naked I was without any money or ID. I asked to borrow a cellphone to call my parents. Refusing to tell him where I was, I managed to get from my dad the number of his friends in Missoula. I hung up and went to get my second ride a little further up the way.

My second ride was from a contractor who regularly travelled between Bozeman and Missoula. As soon as I got into his little blue pickup with bright yellow lightning bolts, he asked me to crack open a beer for him and then told me his life story. Much of it was about his sorrow for a friend who had won a huge insurance settlement and then proceeded to destroy his life with drinking and gambling. From his car I called my dad’s friends in Missoula, who by that time knew I was coming.

When we got to the home I called my parents to let them know I had made it okay, and to ask them to fly me back to Seattle. They insisted instead on coming out and meeting me in Missoula the next morning, and driving back to Seattle together. That worked for me. At this point I felt like I had made my point, that my parents had heard it, and things were on their way to being back to normal. We still needed to discuss betraying each other’s trust, but we could get to that at some point on the road. I took a long shower and shaved the longest moustache I had ever grown.

The next morning my parents arrived and we all went out for breakfast. After our families were finished catching up, we said our goodbyes and got in the car to head back.

My parents looked back at me, and it was the first time we had really seen each other since they got there. They were looking at me like they didn’t know me. They asked me what I was thinking; they weren’t asking so much as expressing the confusion I saw on their faces. I couldn’t understand why they wanted to insist on having the tough conversation right then and there, until I looked around and saw the same escorts that had taken me to Montana walking up along either side of the car. I suddenly realized I was in the back of a two-door coupe, unable to lift the seat up to escape.

I had thought I was free, and now I was trapped again. I was out of ideas and so I turned violent. I grabbed my parents and swore I wouldn’t let them out. I was ready to do more harm, but a part of me watched the situation unfold from outside the car. I could see that I was hurting people who were genuinely trying to help me and loved me and would always put everything aside when I was in trouble. I had hit a limit. I knew what I was doing wasn’t worth the control I was trying to win back, so I let my parents go and attacked the escorts. Thankfully, I was a scrawny 15-year-old kid, and so I couldn’t do much harm. My parents got out intact, and I again found myself handcuffed, headed for the woods.

I eventually gave up cursing and kicking from the backseat, and the escorts and I made peace over McDonald’s.

The full experience

By the time I arrived back in the woods I had decided that my best way out was to finish the program in good faith. In fact, it was a relief to give up on trying to guess how long I would be there and make it go by as fast as possible. This time, instead of just one week to let the haze lift, I got six more weeks to really see.

Montana is known as “big sky country.” On our long hikes through the mountains, the wide summer sky framed everything we saw: eagles perched on cliffs looked like giant boulders before swooping into the valley below; mountain lions took a path along the ridge that ominously intersected with our bearing. Beneath our feet the snow melted, edible glacier lilies and berries spread out, the colour of the rocks shifted from deep reds and blacks to translucent pinks and blues of quartzite and rare lightning glass.

The vastness above our heads and below our feet provided the space for me to unwind all the unaddressed thoughts and intuitions I had numbed out.

I remembered the things I wanted to do and create, the things that sparked my curiosity, but mostly the people that were important to me with whom I wanted to share those things. I understood how I had intentionally broken off relationships as a way to hide from my shame of being a terrible friend. I had such an outpouring of old, packed-away ideas to examine and process that the long walks were never boring.

These intense moments of clarity persisted even in my sleep. Each night as I lay in a bivy sack under my tarp hooch, my thoughts morphed into dreams that were as vivid as real life—my subconscious working out what I couldn’t when I was awake. I once dreamt our group was trekking through a park back home in Seattle and we encountered some of my friends in a circle getting high. I left the trek to go join them and I sat down in the circle just in time for my turn in the rotation. One of the counsellors came up to me and asked, “What are you doing?” I was surprised at how I hadn’t even managed to muster a doubt about rejoining my old life. At the same time, I was also certain it wasn’t what I wanted to do. I got up and got back on the trail. Then I woke up.

—

Looking for an escape?

Dive into Green Screen, a BESIDE Journal that investigates the tension in our modern lives between connection and disconnection, between nature and technologies.

Plus, it’s 30% off for a limited time.Reflecting back

Montana was a pivotal moment in my life. From that experience, I learned a basic lesson: that I want to contribute something positive to the stream of life; that it will not come through anger and fighting, but through understanding of others and giving of myself. While I never did drugs again, I did try drinking a couple months after returning home to Seattle because I thought it connected me to others. I quickly relapsed into my old behaviours of burning up relationships, and within a month I was close to the same isolation I had created before I was sent away. I knew I had strayed from the principle I had learned in Montana and was close to ruining everything I had rebuilt. I also knew my life didn’t have to go that way, so instead of pretending I had things under control and numbing more, I asked for help from people I saw making a positive contribution in their lives. I followed their example, I gave up drinking for good, and I committed to putting this new principle of life first.

I have been sober ever since; I have maintained some of my rebelliousness, but I fight far less (and never with my parents).

As I learned the work of making a contribution (i.e. being an adult), for almost 10 years, I barely got back out into the wilderness—though I kept nature in my mind as a sacred place. I now live in Montréal, Canada, and a few years ago I started to explore the outdoors here with friends.

This last summer, I was in the Québec backcountry with my partner on a small island on a lake. I was thinking about what made the Montana sky so big. We were lying on a boulder, looking up at the stars, hours away from any ambient city light. Without the light pollution of civilization to frame it, the starry sky dropped all the way back behind the silhouette of the surrounding mountains. At that moment I could see with my own eyes how the sky envelops the entirety of earth, and I felt awe at how relatively small me and my made-up problems were. I realized it was the same kind of awe I felt many times in Montana.

Now, no matter where I am—even on a cloudy day in the city—I can look up and have that same experience of the “big sky.” There will never be any running away from it.

Simon Hudson was born and raised in Seattle, WA where he grew up with easy access to the mountains and waterways around the Puget Sound, a thoroughly organic diet, and new agey idealism. In school, he discovered economics and was fascinated by the machinations of capitalism and business. He has been following his curiosity with business ever since, satisfying it with a career in editorial communications. He has been living in Montreal, QC for the last ten years and currently works at Element AI, a company building artificial intelligence solutions for enterprises, where every day he is reminded of just how human business really is.

Never Miss Another Issue

Two issues per year

25% OFF previous issues

Free Shipping in Canada