Atelier

How to cord wood with Claude

Rest just isn’t part of Claude Beaudry’s vocabulary. The busy octogenarian shares some of his know-how and teaches us how to cord wood.

Text—Eugénie Emond

Photos—Alma Kismic

It was over in two minutes. The tree swayed a little, but just barely. With two feet solidly planted on the slope of the ditch and snow up to his thighs, the old woodsman began by making two practised notches in the base of the trunk before quickly getting out of the way. The treetop tilted slightly to the right before gathering momentum and swinging to the left. The aspen collapsed into the sugar bush, exactly where it was intended to, sparing the thin yellow birch that surrounded it.

Laid out along the ground, the tall leafy tree doesn’t even brush the maple taps at the end of the path. Artfully done.

The noise of the chainsaw stops. All that can be heard is Claude’s wheezing. “I have to catch my breath,” he pants. Leaning on his knee, he concentrates on the air that enters his lungs with difficulty. “In winter, I don’t do enough exercise. The sugar season will keep me busy,” he says confidently.

Soon, if all goes well, he’ll be back on his feet in time for long hours spent feeding the fire and adding maple sap to his brother-in-law’s evaporator. Little by little, he’ll get back in shape. But the nights are still too cold, and Claude doesn’t expect the sap to start running for a good two weeks yet.

Once the tree has been transformed into logs and the branches gathered up, he puts his saw away in a cardboard box on the back of his snowmobile. The engine starts and spits out a cloud of blue smoke that trails behind him all the way to his thatched cottage in the heart of the Lanaudière valley.

I met Claude through Raymonde Beaudoin. Raymonde was born in the village of Sainte-Émélie-de-l’Énergie, just like my great-grandfather Jo Coutu, who was once the village butcher, and several of my ancestors. Raymonde writes books about the lives of woodsmen and log drivers of yore. “I think I’ve found someone for you,” she wrote to me.

“Claude Beaudry. He knows everything about tree felling with ropes. He’s talkative and welcoming. He lives on a country road, where he logs with his brother-in-law.”

Claude Beaudry,

the inveterate woodsman

____

I meet Claude on Rang de la Feuille-d’Érable (or Maple Leaf Line), one of the oldest roads in the village, and he is exactly as Raymonde described him. He recognizes the lower part of my face, the Coutu side of my family, even though I’ve never set foot here before.

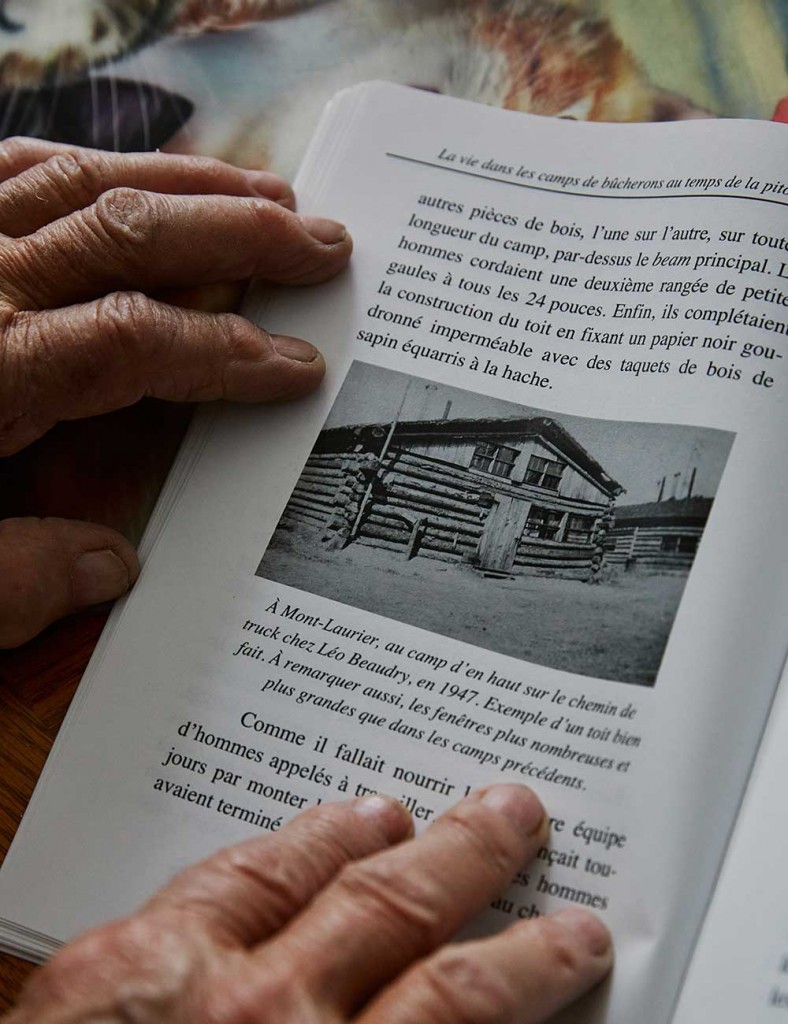

In his study, Raymonde’s book about life in the lumber camps gathers no dust; Claude flips through it from time to time. He opens it now to page 46, where a small black-and-white photo plunges him into reminiscences about fall days when he was growing up.

The picture shows a lumber camp in Mont-Laurier, with log cabins. When he was 18 years old, and for the next two years, Claude stayed here with about 70 other men. That was in 1954. He arrived in September each year and left when the first snows fell: three months of logging from sunup to sundown, with a four-foot-long bow saw, common at the time. There were no chainsaws.

“I would log the edge of the woods, cord, and create a path at the same time. We made seven dollars a cord.”

When he came back from his first trip to the woods, his mother was dead. “She died from the physical toll of bearing 15 children — 13 of whom lived. I found it hard. She was a woman who was always in a good mood.”

And then the world changed. While agricultural businesses were expanding, transforming into veritable industries, his father’s modest and self-sufficient farm was hardly turning a profit.

“My father offered it to me, but at the time it wasn’t enough; I couldn’t make a living from it.”

If he had accepted his father’s offer, Claude might have saved himself his long interlude of city life: 40 years in Montréal, where he joined the rest of his siblings. He left the bow saw behind and became a plumber — one plumber with Herculean strength:

“I could carry a 200-pound cast iron bathtub: I would stand it up, carry it on my back, my head resting against the hole in the bath. I could go up three storeys with it. The guys in the city found this tremendous!”

Returning home

____

Claude has just finished his story when the walls of the little house start to vibrate. “Here we go! It’s starting!” says Suzanne, his companion of the last 20 years. With a loud roar, a large piece of snow falls off the sheet-metal roof. “The snow’s coming! It’s getting milder!” Claude reassures me when he sees my alarmed glance.

Calm once more, the birds return to the feeder near the window. Nuthatches, grosbeaks, and chickadees. “Yesterday we saw an all-white one with a little red thing on its head,” says Suzanne. Since he came back to Sainte-Émélie-de-l’Énergie, to the country road of his childhood, Claude never tires of daily contact with nature. “Le Rang de la Feuille-d’Érable never left my mind.

“I made my life in Montréal, but to grow old there? I wasn’t interested. Here, there’s something to do: fell trees.”

When he retired, and his wife “took off,” ending their long relationship, Claude came back home. He bought some land near Chemin Beaudry (which was named for his family). The house was just a gable-roofed cottage that he built in the 1970s, where he sometimes came with his sons on weekends.

“I paid 500 bucks for the land. In the early 1970s, it wasn’t worth 10 cents a foot.” He added an extension and certain amenities. For a few years now, he’s been helping his brother-in-law who owns a sugar bush on the huge patch of land nearby. “My brother-in-law was an office guy, not a woodsman at all, but he works hard, and he wanted to learn. I showed him how to fell a tree.”

While Claude reminisces, Suzanne sits at the table, focused on a canvas portraying a shining raccoon. “It’s called painting with diamonds. You glue beads according to the colours in the numbers. I do it with tweezers.”

It’s a painstaking task — one that helps pass the long winter days. It couldn’t be further from Claude’s favourite pastimes. Despite his asbestos-weakened lungs, he rarely sits down for any length of time.

“When there’s nothing to do, I tell you, he’s like a bear in a cage,” says Suzanne. “He looks for something to work on. He’ll even cord snow!”

“Ah! It’s not so bad as all that,” grumbles Claude. “But I will say: since I got here, I’ve never stopped working. And that’s exactly what I wanted,” he adds, satisfied.

—

SAVOIR FAIRE

Knowledge from our elders that have the potential to equip us for the future.

BUY (In French only)Miniguide

How to cord wood

____

The best time to fell wood is at the end of autumn, when it’s not bursting with sap and it offers less resistance. Every year, Claude brings the logs he split in the sugar bush the previous season down to the basement — some from several birch trees, most of them ravaged by parasites. The wood dries for several months, sometimes an entire year, corded outside, before being used for heat.

Storing it in cords (under a roof or a tarp, sheltered from weather) allows you to keep it from rotting while also saving space. But you have to know how to do it: stacked incorrectly, the pile will tumble like a house of cards. Claude’s cords are made of two pillars of logs, one at each end, which stabilize the whole.

The price of a cord of wood varies from one region and one seller to another, but their dimensions remain standard (four feet high and eight feet long). Claude tells us that the shrewdest sellers leave holes in order to make more money.

- Place three logs of the same size on the ground, parallel to each other and closely aligned; this forms the base of the first pillar. The wood that’s in contact with the ground must be placed with the bark against the earth in order to protect it from moisture.

- Stack two or three logs (still the same size) perpendicular to the first, ensuring that the construction is stable.

- Repeat the preceding step until you’ve got a four-foot-high tower (a little more than a metre tall).

- Build a second pillar eight feet (a little more than two metres) from the first.

- Between the two, place logs beside each other, parallel, nesting them firmly, until they reach the height of the pillars.

- If the structure moves or leans over time — which can happen after a few months, since the ground shifts — rebuild the cord of wood, in whole or in part, as needed, to recreate stability.

Eugénie Emond is an independent journalist. She is also finishing her master’s in gerontology at the University of Sherbrooke. This year, her work was awarded two Grand Prizes for independent journalism and a gold medal at the Digital Publishing Awards. She is the author of SAVOIR FAIRE: Histoires, outils et sagesse de nos grands-parents, in which this portrait also appears.

After an eclectic beginning to her career, Alma Kismic has lived off her passion, photography, for the past five years. Each of her portraits demonstrates nuance, authenticity, and warmth. Alma also has a great love of nature, textures, and human beings—all of which are sources of inspiration in her minimalist works.

Never Miss Another Issue

Two issues per year

25% OFF previous issues

Free Shipping in Canada