Away

Slowed to a Crawl

Notes on the movement of waves, the web of life, and a certain stillness, found somewhere along the St. Lawrence River.

Texte & photos — Maxime Fecteau

What was it that had so troubled me about the incident?

Was it that spidery indifference to the human triumph?

— Loren Eiseley

It’s early September and the cold air reads above 20 knots on the anemometer while the bow thumps down large, cresting waves. To starboard, my crewmate at the helm squints at the town of Saint-Siméon in the distance. It’s distressingly clear to everyone that the town has moved very little in almost three hours, a flawless reminder of just how perfectly the three of us are standing still on the surface of the St. Lawrence River. We’re moving, to be sure, but we don’t seem to be moving forward much, and we’re very, very wet. The motor is gunning to its limits, letting out a much louder whir than we know we can safely afford in the long run. And whether we opt to travel straight upriver, into the headwinds, or try to tack upwind under some press of sail, it makes no difference at all. Every inch of ground we gain is just as quickly thwarted by choppy waters, currents, and a full-blown falling tide.

The marina we’re headed for, Cap-à-l’Aigle’s “port of refuge,” is our only possible destination for the day and, though my phone estimates a 21-minute drive from Saint-Siméon, we’re just hoping that our slow crawl along the river lasts only three more hours.

Our captain, Roger, turns his gaze anxiously toward the ship’s bow, and in an instant I realize what he’s thinking: in the rough waters, the anchor is at risk of falling overboard and striking the hull. Given the budding chaos of our return journey so far, this worst-case scenario seems both natural and inevitable. And we’re still six or seven days from home. I jump up from my seat in the stern and rush toward the foredeck. Running on adrenaline, I make a series of hurried steps, pass the shrouds to port, and, reaching the very nose of the boat, I stop for a brief moment to catch my breath. But before I have a chance to bend over and lay hold of the anchor, the boat crashes deeper than ever into the trough of a wave. In a flash, I lose my footing and fall flat on the slippery deck, like a fly slapped right out of midair.

And it was then, for about the dozenth time since we’d left Montréal a week earlier, that I came face to face with the elegant work of a spider. Washed out and breathless on the deck, I opened my eyes to a delicate web just a few inches above my head. I noticed how the resilient silk fluttered through the same squall that put me on my back. Part of the web was damaged, somewhat collapsed onto itself, but still it upheld a constellation of fine droplets which glistened as the boat slammed and crashed into the waves. I lay mesmerized for a short while. That web is making it through the storm.

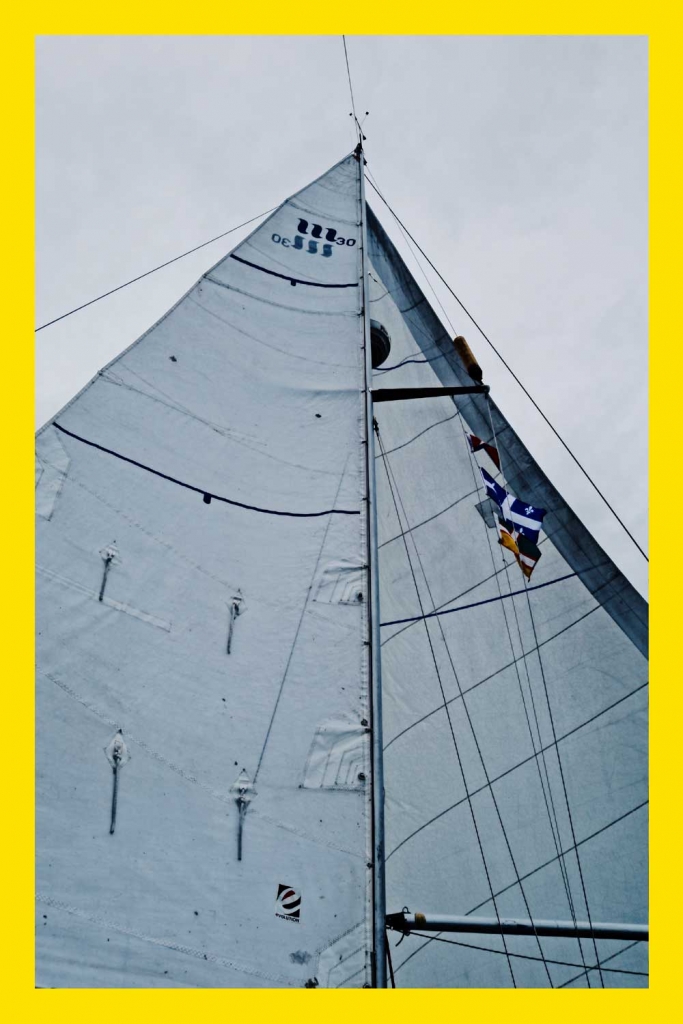

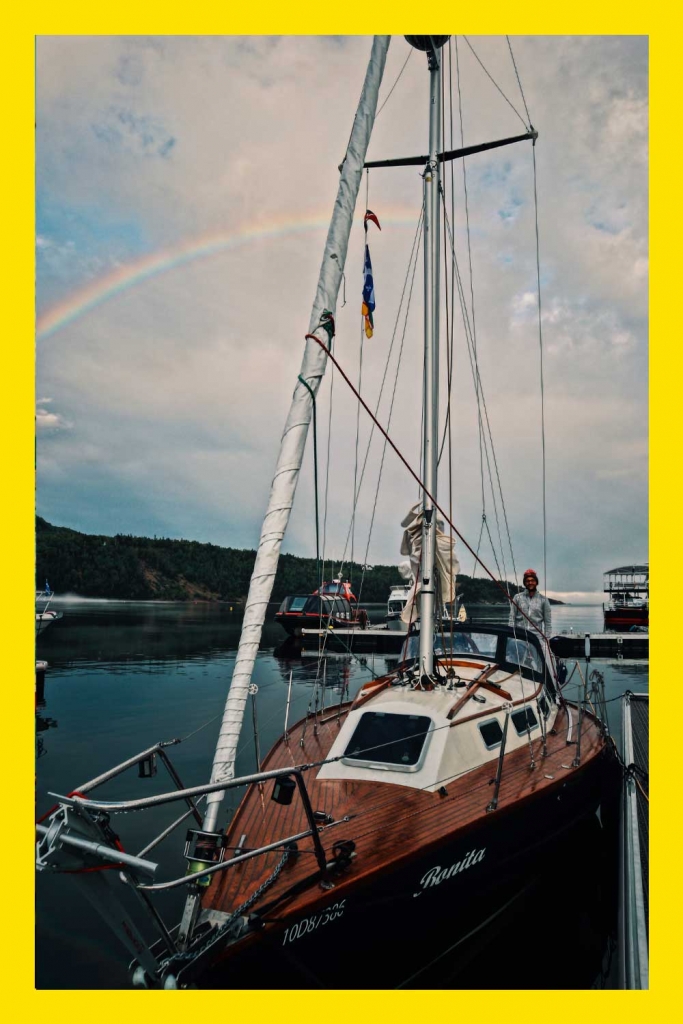

From the outset of this two-week sailing trip, right up until its very last moments, spiders were a constant presence. On the cab ride to the yacht club the night before we left the dock to head downriver, our driver said something proverbial and lovely, which I stored away in my phone: “Humans beings are like spiderwebs, you know — we’re fragile, but we’re also tenacious, all at once.” And with that ringing in my ears, we boarded Bonita, an aptly named 30-foot, royal-blue-hulled yacht that lives on Lake Saint-Louis, the body of water that borders the island of Montréal to the south, whose shores are known for their particularly healthy population of arachnids. As our first day broke scarlet red and we left our home port, I made it my number-one task to tiptoe around the deck and wave my hands between lines, pulleys, and shrouds, clearing away the multitude of cobwebs.

Within a few hours we’d watched Montréal’s skyscrapers shrink behind us; within a few warm days of clear blue skies and fair winds, we’d made it all the way to Tadoussac. Still every inch according to plan, we then pierced the thick mist at the Saguenay fjord’s mouth, accompanied on all sides by beluga whales. We sailed our way up amid soaring cliffs and a perfect balmy atmosphere.

We were progressing swiftly from our spiders’ home turf, but still I don’t think there was a single morning when, waking before sunrise and turning on the little lamp at the top of my berth in the forepeak, I didn’t catch an eight-legged creature resting atop a valley in my sleeping bag or, a little later, crawling across the counter while I brewed a first pot of coffee. Once, before going to bed, I spotted a spider lightly dangling down its own floss, hanging out in the open, right in the middle of the main cabin. While I brushed my teeth, I watched its fine legs work their way up and down in space. Eventually I pinched the silk halfway between the ceiling and the tiny moving thing and carried it outside.

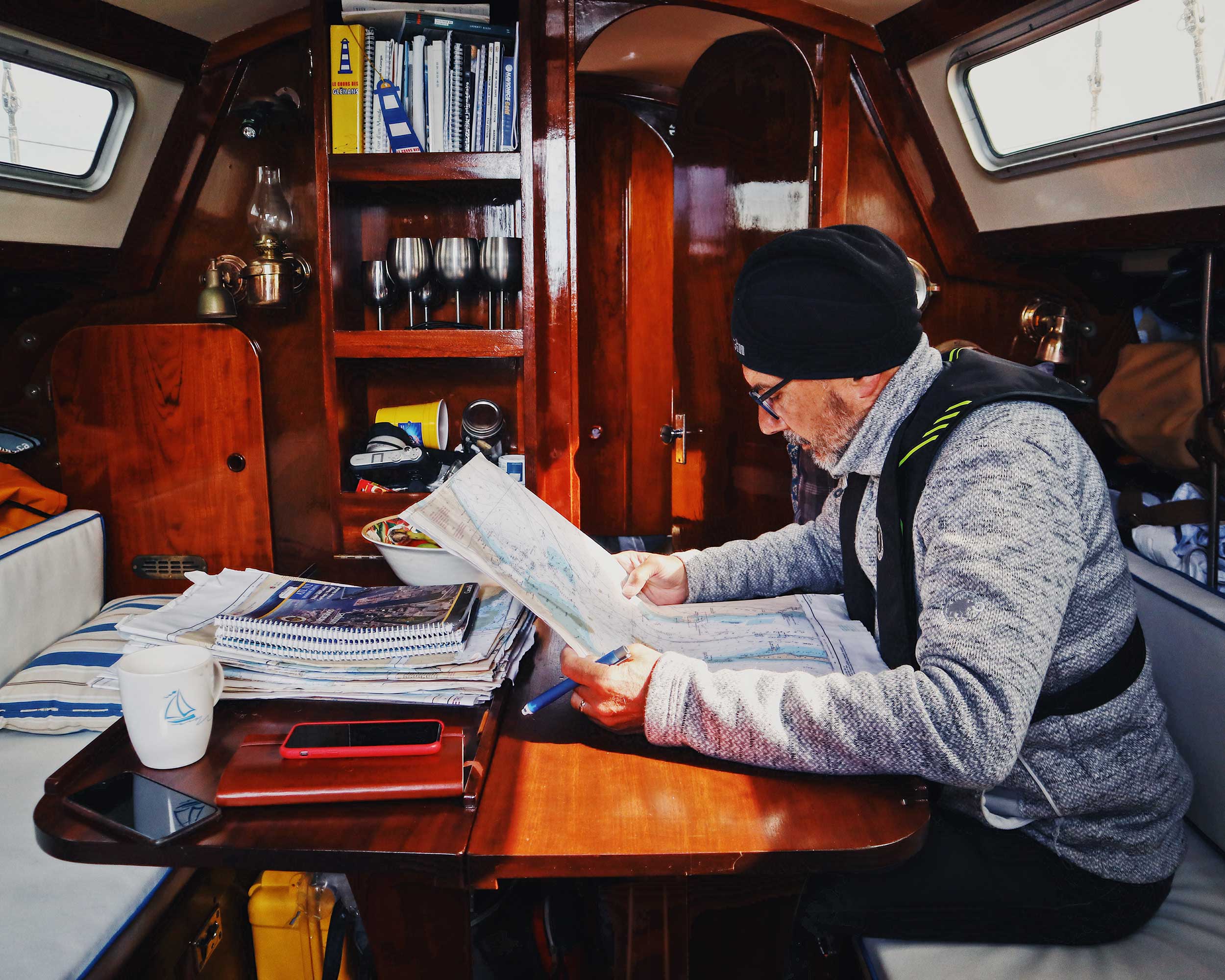

The night before we left Tadoussac on our way back upriver to Cap-à-l’Aigle, we sat together around pints at the village pub. Running through our timetables for the area’s tides and currents and checking differing wind forecasts on our phones, we charted out the next day’s travel, approximating how every variable would likely come into play at every hour. Gradually, we managed to convince each other that we’d come up with the optimal departure time and best overall navigational strategy. Hungry for a dinner we still had to prepare, the three of us walked out of the bar into the dim light of the street, feeling, in retrospect, a tad too self-assured. We strolled downhill toward the docks.

“Guys, what about Dorian?” asked my crewmate and old friend Laurent, peering at a news notification from the screen he held in his palm. “It’s not quite a hurricane anymore, but … it is about to hit Nova Scotia.”

I noticed, as he said those words and Roger came to a halt, slowly turning himself around, that the air was not only chillier, but also significantly more agitated than when we’d come up the same street an hour before.

About an hour later we were seated around the table in Bonita’s main cabin, grating cheese over our dinner plates, when I looked out and up toward the mast, becoming aware of a whistling sound gathering force above us. Laurent stuck his head and hands out the hatch and turned on the anemometer, and our eyes went wide. The wind was blowing at 30 knots … 31 … 34! Roger said what we were all thinking: “Thank God we aren’t moored somewhere out there.”

That night the wind blew so intensely, in such blaring gusts, that it proved virtually impossible to drift off into sleep. After fighting sleeplessness for a long while, I eventually reached for my duffel bag and pulled out a book. I’d brought The Unexpected Universe, a collection of essays by Loren Eiseley, a perceptive anthropologist whose personal and lyrical descriptions of the natural world I find especially intriguing. That night I happened upon “The Hidden Teacher,” an essay wherein Eiseley contemplates his encounter with an orb spider sitting at the heart of her web. After grazing a strand of silk with the tip of his pencil and watching his teeny friend “fingering her guidelines for signs of trouble,” he comes to the understanding that the web allows for an extension of the spider’s sensory experience, much as humans chart their world outward from their own experience:

The spider was a symbol of man in miniature. The wheel of the web brought the analogy home clearly. Man, too, lies at the heart of a web, a web extending through the starry reaches of sidereal space, as well as backward into the dark realm of prehistory. His great eye upon Mount Palomar looks into a distance of millions of light years, his radio ear hears the whisper of even more remote galaxies, he peers through the electron microscope upon the minute particles of his own being. It is a web no creature of earth has ever spun before. Like the orb spider, man lies at the heart of it, listening. Knowledge has given him the memory of earth’s history beyond the time of his emergence. Like the spider’s claw, a part of him touches a world he will never enter in the flesh. Even now, one can see him reaching forward into time with new machines, computing, analyzing, until elements of the shadowy future will also compose part of the invisible web he fingers.

The following afternoon, the storm raged. After what felt like an age flat on my back on the ship’s deck, in sudden, full contemplation of my place at the center of so many forces, I finally picked myself up and, thankfully, caught the ship’s precarious anchor before it fell. The day proved to be one of the most exhausting sailing days of my life, and I was relieved when we finally made it to Cap-à-l’Aigle — all of us were.

That night, I walked around the harbour to find a quiet spot where I could lie under the starry sky, at the edge of a stone pier. I spent a little while alone, listening to the sound of a relaxed St. Lawrence River.

Then I pulled out my phone from my pocket and typed my first and only journal entry from the trip:

It seems Dorian missed us by an inch, and I’m left wondering if there’s any real difference between a hurricane’s motion and my hand brushing through a spider’s web. Maybe the realization I came to, the feeling that swept over me in that eye-of-the-storm moment today, had to do with how vastly small I really am in the greater realm of things. It was the littlest I’d ever felt, as if the web, and Eiseley’s words, had filled me with a telescopic sense of my place in this world. And maybe ever since I started messing about in boats, as a small child on my parents’ keelboat, I’ve savoured the motion of sailing because it allows me to feel myself as a minuscule body in a whole cosmos of forces and elements: a teeny little moving thing which is working always, as much as possible, with the flow — with occasional exceptions, like today’s gruelling final six hours on the water. Like many others, I’ve been on a long hike to reach a mountaintop and look deep into a valley beyond. Once, I was even lucky enough to see out the window of a helicopter while slowly descending into the Grand Canyon. And, of course, I’ve had my fair share of staring competitions with the myriad stars across a truly dark, country sky, wondering as we all do about the breadth of it all. There are infinitely many ways to feel how far our lives might extend, in the end. Yet nothing for me quite beats sailing. Nothing is really quite like feeling yourself as a microscopic part of the dance, the works, the flow — yet another faint vibration moving through some part of the web. Even washed out and breathless on the deck, even — or perhaps especially — while fluttering through the squall.

Maxime Fecteau savours the sound of water, particularly when it splashes or gurgles against the hull of a sailboat. An avid reader of literary nonfiction, he is otherwise a student of the personal essay and nature writing in American literature. His book Fragments d’un enfant du millénaire (Nota bene) will be released in the fall of 2020.

Never Miss Another Issue

Two issues per year

25% OFF previous issues

Free Shipping in Canada