Dossier

The People’s Forest

The Falaise Saint-Jacques was an orphaned urban wildwood in the heart of Montréal, until a motley crew of passionate volunteers decided to make it their own.

Text—Mark Mann

Photos—Guillaume Simoneau

If the weeds and invasives of Montréal had a god, it would be the Falaise Saint-Jacques. Nine storeys tall and three kilometres long, the narrow forested escarpment hunches over Highway 20 at the entrance to the city, absorbing the dust and roar of traffic. Every day, 300,000 people drive past the Falaise, but if you were to ask them about it, they’d likely reply, “What’s that?”

It is a strange sort of vanishing act, to be seen and ignored by all. First planted in 1982 on what had been an ad hoc dumping site, this rugged stretch of woodland has never received any sort of consistent or meaningful upkeep by the city. Until recently, vanishingly few people ever visited it.

But human indifference has been the forest’s good fortune. While no one was looking, it evolved into a jungle-like ecosystem, bursting with tall trees and birdsong.

Today, it provides a refuge for foxes, groundhogs, an endangered species of brown snake, and the occasional deer that wanders in along the nearby train tracks.

It’s easy to fall in love with the Falaise, how it feels huge and lush and yet like a secret garden. Since 2015 some of its admirers have been filling the void left by the city by taking care of it themselves: carrying out hundreds of tires and other trash by hand, clearing pathways, documenting wildlife, and filling bird feeders. They call themselves Sauvons la Falaise—or “Let’s Save the Escarpment”—and their motto is “Make the Falaise our own.”

In many ways, the members of Sauvons la Falaise have succeeded beyond their wildest dreams. The city and the province are investing millions to protect the Falaise and dramatically increase the amount of surrounding parkland, with the vision of turning the escarpment into a hub for a sprawling network of green corridors around the city.

But as these transformations unfold, the forest’s most ardent admirers are wondering if their wild oasis will retain the sense of freedom and community they have experienced there. In short, is it still theirs?

Crossing to the other side

____

On a cold February day in 2015, a librarian named Lisa Mintz was walking home after work when she heard the screaming of crows from beyond a nearby treeline. Though she didn’t yet know it, Mintz’s route took her along the top of the Falaise on a rundown industrial street called Saint Jacques. The crows she was hearing were part of a massive murder that descends on the escarpment every winter, clouding the bare branches of the cottonwood and box elder trees. She decided to investigate.

For the uninitiated, entering the Falaise is no easy feat. That part of Saint Jacques Street presents a long barricade of auto repair shops, car dealerships, and hardware stores. The forest is visible beyond their back parking lots, but to reach it you have to get past a chest-high chain-link fence, after which the escarpment drops away steeply.

Mintz, a budding birdwatcher who’d taken to carrying her grandfather’s old binoculars on her walks, was not the type to be dissuaded. With a bit of searching, she found a hole in the fence and crossed into the thick bramble on the other side.

Night was falling as she began her descent into the Falaise, her hat pulled low over her voluminous red hair. Stomping and sliding through the snow, she quickly realized she would have a hard time reaching the top again. The forest felt untamed and deserted, and she became scared. “Can I actually get lost back here?” she wondered. At last, she came across a pair of ski tracks running along a narrow trail and followed them out to make her escape.

That first adventure would prove fateful both for Mintz and for the Falaise, which has a way of inviting deep devotion from the people who stumble into it. In the years since, Mintz has brought thousands of people to discover the forest, and many have joined her army of volunteers and advocates. But the best part of the experience was the sense of solitude.

“Back then, you felt like the first person that was ever there,” Mintz says.

Just a hundred metres away, however, she could hear the noise of construction on the new Turcot Interchange, a $4 billion public infrastructure project to rebuild a criss-crossing network of highways and train tracks.

The creation of the original interchange back in the 1960s had dramatically altered the geography of the escarpment, when the slopes of the Falaise were steepened into cliffs by trucks dumping excavated dirt from the top. The renewed construction threatened to change the Falaise again.

Yelling and screaming

____

While walking in the forest in 2015, Mintz noticed orange markers on a large stand of trees at the western end of the escarpment. Alarmed, she called her city councillor, Peter McQueen, who represents the Notre-Dame-de-Grâce neighbourhood north of the Falaise. A passionate cross-country skier and one of the escarpment’s most devoted users, he had made the tracks that Mintz found on her first trip into the Falaise.

McQueen recommended she attend a public consultation meeting for the Turcot project the following evening, where she was assured that the trees wouldn’t be cut. But when she returned to the Falaise a few weeks later, they were gone.

“I was destroyed,” Mintz recalls. “It was the most horrible thing I’d ever seen. They lied to me! Blatantly!”

In all, Québec’s Ministry of Transport (MTQ) removed 140 trees, and also acquired a voluble opponent in Lisa Mintz. “The first thing I did was I yelled and I screamed,” she says.

Mintz quickly formed Sauvons la Falaise on Facebook and penned an op-ed for the local English newspaper, the Montreal Gazette, in which she decried the MTQ and “the environmental destruction that is taking place right before our eyes.”

The removal of those 140 trees and the development of that area may have been even more destructive than Mintz realized at the time. One quarter of the felled trees were Prunus americana, or wild plum trees, indicating the likely presence of a historic Iroquois village, says Katsi’tsahén:te Cross-Delisle, an archaeological consultant and a representative of the Kanie’kehá:ka Nation.

Some of the other trees in that area were beech and hickory, whose nuts the Kanien’kehá:ka preserved and ate. Settlers forced the Kanien’kehá:ka off the Island of Montréal, or Kawenote Teiontiakon, in the late 17th century. The south-facing slopes of the Falaise create a warm microclimate that would have made it an ideal place for a settlement

and an orchard before then.

Though few people had heard of the Falaise or ever visited it, Mintz’s article drew a lot of attention. The next time she came to a public consultation with the MTQ, she was joined by a band of 20 or 30 supporters carrying signs, who in turn drew the attention of even more journalists and news stations.

Sauvons la Falaise has since swelled to 400 members, and they have kept sustained pressure on the province and the city. Since she started fighting, Mintz has given over 300 media interviews about the escarpment.

The forests eyes and ears

____

There are two types of people who visit the Falaise: the noisy ones, like Mintz, and those who prefer to stay quiet about it. The latter type tends to appreciate the escarpment for the very qualities that its new official status will likely imperil—namely, that it feels unsupervised and free.

During the first summer of the pandemic, a group of teenagers carried in bags of cement and hand-built an entire skate park among the trees, pouring the forms for rails and ramps on a less overgrown stretch of the old service road. They made a sitting area with tables and chairs pulled from the forest and set out cardboard boxes for empties. A spray-painted skateboard hung from a tree branch announced the name: Locals Only.

“People that I hang out with are always drawn to those kind of areas, where you feel a little bit secluded from everything and there’s a bit more freedom,” says Montréal artist Junko.

who creates giant, semi-organic sculptures in disused lots and other liminal spaces around the city. “Maybe you have the time and space to do something that you couldn’t do when there’s a lot of people around.”

Junko helped build the skate park, and later that winter he returned to the Falaise to undertake the construction of a massive mechanical beast out of logs and car parts. Poised like a panther mid-prowl, the creature rises 5 metres tall and 10 metres long, a perfect symbol of the Falaise’s unexpected scale and lawless charm.

Though their interests and motivations differ, the members of Sauvons la Falaise have made common cause with folks like Junko and the skateboarders. Last summer, Mintz ceded control of Sauvons la Falaise to a new steering committee made up of three men in their sixties—the joke is that it takes three men to do the job of one woman. They all love the skate park and Junko’s creation, which they’ve dubbed “the Falaisosaur.”

“There’s a lot of artwork that’s being built along the trails,” says Malcolm McRae, a steering committee member. “We encourage this.”

McRae marks the different artwork on a custom Google Map so visitors know where to look, though his own contributions to the Falaise lean more toward filling bird feeders, dragging out trash, and updating the website. The retired engineer has been the main “boots on the ground” for the group and has led several cleanup days, during which as many as 90 volunteers have carried out more than 400 tires and lots of other junk.

Sauvons la Falaise may have started with a focus on advocacy, but the group has evolved to take on more and more of the forest’s direct care and maintenance. McRae and the other members of the steering committee, David Gamper and Roger Jochym, have spent the last two summers creating a walking trail that reaches from one end to the other.

Louise Chenevert, the group’s resident tree expert, has put up dozens of laminated signs to mark notable tree species and warn visitors away from poison ivy. Volunteer biology students at Montréal’s Concordia University have been meticulously documenting plant and insect species and conducting soil tests.

The members of Sauvons la Falaise are the forest’s eyes and ears on the ground. They keep track of the dumping of salt-laden snow over the edge in winter, the weight of which destabilizes the earth and knocks over the trees. Because of these incursions, the forest has been slow to mature into a more biodiverse ecosystem.

But people like Chenevert also track signs of hope, like the appearance of Sanguinaria canadensis, or bloodroot, a fragile spring flower that has traditionally been used by Indigenous peoples to make a red ink. She took me to see what she thought was a single specimen, but when we arrived at the spot she gasped and called out, “Oh my god, hello!”

Near the path were half a dozen bloodroot plants, each one a good omen for the Falaise. “Yeah, so this is awesome,” she said.

A new battle

____

Now, thanks in part to advocacy by Sauvons la Falaise, things are changing for the Falaise Saint-Jacques. Around the world, urban forests are increasingly recognized for the innumerable benefits they confer—reducing air pollution, temperatures, and crime, and improving general well-being—and the City of Montréal has taken special notice of this unique specimen right on its doorstep.

In 2020, Mayor Valérie Plante announced the creation of a 60-hectare nature park that will encompass the escarpment, dramatically extend the amount of green space, and provide new walking and cycling paths.

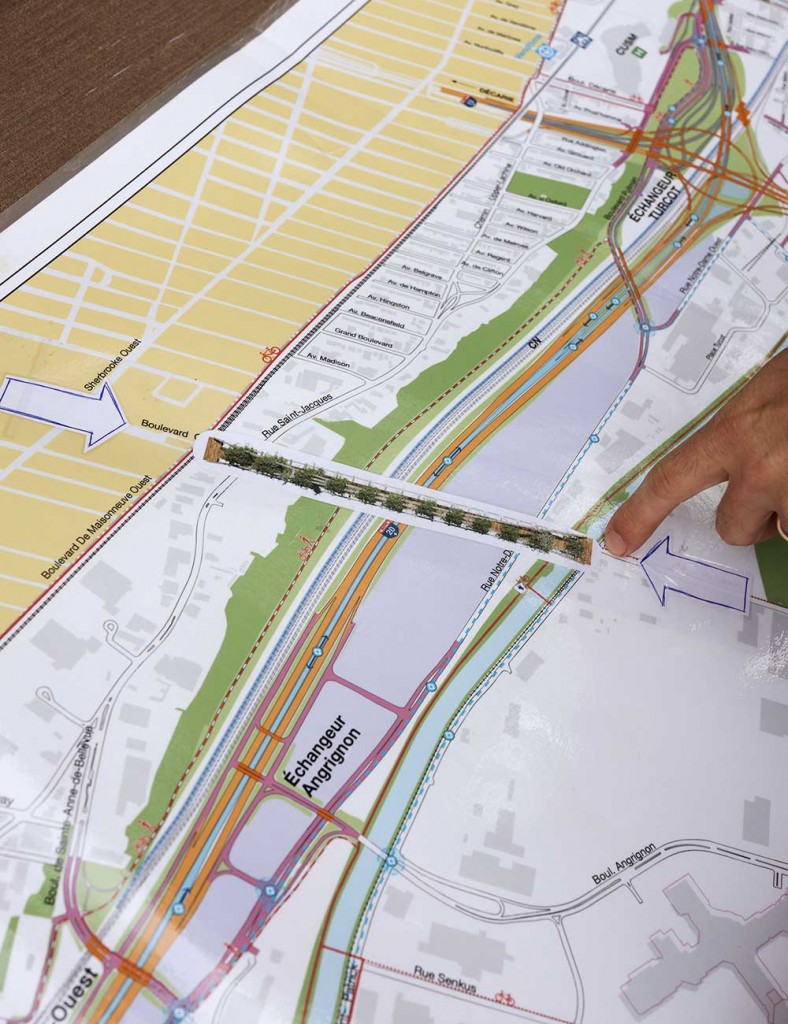

These transformations are still only an initial step toward an even bigger plan to recast the Falaise as a giant billboard for Montréal’s ecological grandeur and make it a key link in a vast network of “green corridors” that will connect different parks and neighbourhoods. These corridors, or bandes vertes, are a signature component of Montréal’s 10-year, $1.8 billion green revitalization plan.

In the summer of 2021 Transports Québec created one such green corridor along the base of the Falaise, next to the train tracks. Workers planted 2,800 trees and more than 60,000 shrubs and grasses over an area of 13 hectares, nearly doubling the size of the forest.

“They actually did a really good job,” Mintz concedes. “It’s native species. It’s mixed forest. The trees they planted are quite large.” She even sent them a nice note.

But the process has been fraught. While creating the green corridor at the base of the Falaise, the province drained an important wetland that ran nearly its entire length and replaced it with a dry ditch.

Only one small pond remains. If the wetlands were the lungs of the escarpment, now it’s breathing through a straw.

There doesn’t seem to be much chance of bringing back the wetland, but Mintz and Sauvons la Falaise haven’t given up fighting. Their main struggle now is to secure the construction of a land bridge, dubbed the Dalle Parc, that will extend from the top of the escarpment across the highway, where another new park is slated to be built on disused land.

The province promised to build the Dalle Parc and then backtracked on the plan. Sauvons la Falaise and many other local groups teamed up to revive the project, and they appear to have been successful, though it still faces uncertainty and delays. Mintz and the other supporters of the land bridge have sworn not to give up until it’s built.

Protecting the magic

____

The first time I visited the Falaise was in the spring of 2021. I had found it on Google Maps by scrolling over the city in Satellite view—like other neglected green spaces, the Falaise looks grey in Street view—and decided to go check it out.

At that time, the brunt of the cleanup by Sauvons la Falaise had yet to be done, and none of the new trees or bushes had been planted on the new adjoining “green corridor.” Entering the forest still felt like trespassing. It was wonderful.

A blanket of Virginia creeper and wild grape vines covered everything, engulfing the tree trunks and hanging from branches in long ropes as thick as your arm. The overgrown path was crisscrossed with fallen logs, and along the way I found scattered firepits with makeshift seating around them. Coming across Locals Only, it felt like I had walked into a post-apocalyptic tiki bar.

But going back into the Falaise a year later, the little camps are all gone and Locals Only has been dismantled. The trail is well-maintained and marked with handwritten signs by McRae, Gamper, and Jochym. Chenevert’s species identification guides flutter in the wind where they have been tied up with brown string.

It all still feels charmingly DIY, but the culture of the Falaise is shifting.

Mintz anticipated these developments and is trying to shape the next phase in the life of the Falaise, so that more is gained than lost from its newfound accessibility. “We can be the people who are stewarding this place,” she tells me.

She has launched an environmental education organization called UrbaNature, whose activities are primarily focused on the Falaise. They lead informative and wellattended tours in the escarpment year-round. Once more funding rolls in from the city, UrbaNature also plans to organize citizen brigades to pull out invasive species and replace them with native plants.

Still, she has her fears. “My worst nightmare would be for the city to decide that it all needs to be cleaned up.”

For Mintz and her allies, the new parkland the city is creating nearby can be more like traditional green spaces, but the old forest should be treated differently. “We see the Falaise being left alone and just used for educational purposes.”

Junko and his friends are also anxious about the Falaise’s newfound status and popularity. “It would take away some of the magic that place has,” he says. “The majority of the city is extremely accessible and populated. What makes that area special is that it isn’t.”

Seclusion is certainly part of the Falaise’s charm, but it didn’t really come to life as a unique and enchanting place until a whole community of people adopted it. It may take a city to make a park, but only citizens can keep a forest wild.

Mark Mann is the associate editor-in-chief at BESIDE. He has previously written long-form features for the Walrus, the Globe and Mail, Toronto Life, and many others.

Guillaume Simoneau is a Montréal-based photographer whose work has been exhibited in galleries and museums around the world. His photographs have been collected in four monographs: Murder (MACK, 2019), Experimental Lake (MACK, 2018), Love and War (Dani Lewis, 2013), and La Commande du Morse (Éditions du Renard, 2013).

Never Miss Another Issue

Two issues per year

25% OFF previous issues

Free Shipping in Canada