New Narratives

Tiny Toes

Being 30, caught between the biological clock and the urgency of climate change.

Text—Blanche Gionet-Lavigne

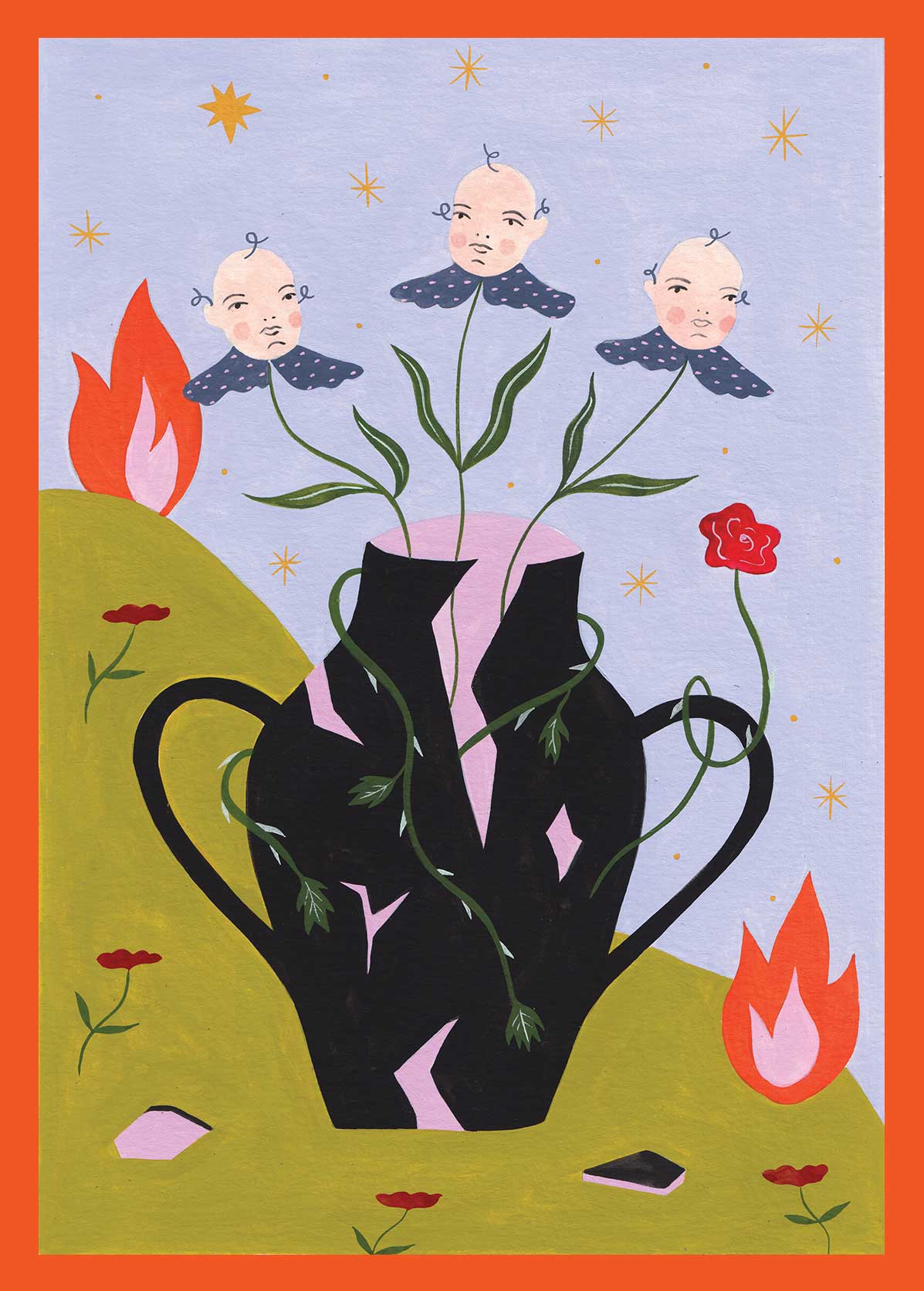

Illustrations—Estée Preda

I’ve always been surrounded by childhood. My parents dedicated their professional and artistic lives to a youth theatre company. They are tellers of stories in which realism and magic are mixed together.

In my parents’ eyes, children are the poets of the real.

Their company’s most successful production was called Tiny Toes. The piece tells the story of a day in the life of my sister as she awaits an event that will shake up her world: my birth. I remember staring, fascinated, at the poster for the show, where a series of toes appeared with little smiley and sulky faces.

I always thought I would have kids. I was convinced that when I turned 30, my troubles would be less heavy, my mind would be lighter and turned toward a clear future. One day, tiny shadows would walk confidently alongside my own. I would be their sentinel, the one who’d make them feel safe and guide them down this winding road.

Over time, though, these tiny shadows began to scare me. My throat was tight with having reached child-bearing age. The mere act of checking my Instagram account could disturb my mood for the rest of the day—all my friends’ photos of little toes stressed me out as much as rush-hour traffic.

Sometimes I would imagine them with a mouth, as on the poster for my parents’ show. The mouths shouted that my time had come: that to be fulfilled as a woman, I needed to become a mother myself.

⁂

I always thought I would have kids. I was convinced that when I turned 30, my troubles would be less heavy, my mind would be lighter and turned toward a clear future.

I am anxious by nature, and writing calms me down. I find my worries much more entertaining on paper. I recommend this exercise to everyone: it’s soothing and costs less than a shrink.

The year 2018 was marked, for me, by my work on the documentary play Entre autres, a collective project that examines the different points of view that inform Québécois society. I became particularly interested in the difficulty humans have in addressing climate change. This had a therapeutic effect; the show quieted the little voice that murmured to me about an obligation to procreate—but with arguments that I hadn’t anticipated.

I didn’t have a choice; I was forced to question my own relationship to nature, to examine my convictions, and was pushed outside my comfort zone. Like an explorer in a foreign country, I found myself in places I never thought I’d go.

⁂

A Partial Itinerary of Evolving Worry

August 2018

I argued on Skype with a climate-change skeptic who boasted about having the cleanest recycling bin in the city.

September 2018

I struck up a friendship with the director of communications of a previous Minister of the Environment, an unabashed climate-change denier.

October 2018

I went to a rally for the right-wing Coalition Avenir Québec on the night of the elections and passed myself off as a party supporter. I spoke with one of the collaborators on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change when their latest report came out.

November 2018

I cried when I saw the mountain of debris at the recycling sorting centre.

DÉcember 2018

I was part of a radio round table on environmental guilt. I can now proudly consider myself a specialist in feeling guilty.

January 2019

I chased down theatre director Dominic Champagne after the release of his polarizing online climate-change pledge, The Pact for Transition. I drank herbal tea with a group of survivalists in northern Montréal. I spoke with psychiatrist Marie-Ève Cotton about the human brain’s difficulty comprehending long-term threats. I began to mistrust my own thoughts. I went to the last screening of Anthropocene by Edward Burtynsky, a film of a vertiginous beauty. I got anxious. I got anxious often.

⁂

“We’ve already hit the wall.”

“Imagine, Blanche: when you’re 60, in 2050, the Greenland ice sheet and the permafrost will have melted, sea levels will have risen so high that hundreds of millions of people will have had to move. It’s going to create violence, and chaos—it will be post-apocalyptic. And the majority of people are asleep at the wheel right now!”

“The idea is not, ‘We’re in a wide river and we have to row upstream.’ The idea is, ‘We need to reverse the water’s current!’”

There are certain words that strike us, and that we never forget. For six months, I took this information in. It was impossible not to feel concerned.

Bit by bit, I lost the desire to look ahead. I couldn’t go back and continue to see things as I naively saw them before. I felt like a nearsighted person who had just been offered her first pair of glasses.

This conversation left a funny taste in my mouth. A mix of veggie pâté and the end of the world.

What I came to understand is that in order to avoid climate catastrophe—to reverse the water’s current—we would have to radically change our way of life. But what kinds of changes are we talking about, exactly? The answer I got to this question was, “Consume less to live better.” Fair enough, but I wanted more concrete answers. It was starting to seem like every-one I spoke to would prefer to avoid them. Or almost everyone.

⁂

At the restaurant Vego on Saint-Denis, Blanche sits with Josée, a well-known columnist, at a table at the back of the room.

JOSÉE, leaning toward Blanche as though to tell her a secret

I have a child, and I have to say, I regret now bringing him into a world like this. Because I can’t find my way to hope. We’re not making any progress!

BLANCHE, staring at her plate of veggie pâté

Do you think hope would be harmful?

JOSÉE

Harmful—I’m not sure. But the fact remains that the best thing we can do for the environment, according to several studies, is to have fewer children. But people aren’t ready for that. People are ready to buy a bamboo toothbrush.

BLANCHE—Because it’s a huge decision! I’ve been convinced for a long time that I wanted kids. Just thinking about giving up the idea of motherhood for good makes me want to break something.

JOSÉE—Well, yeah, because it puts the meaning of life into question. You’ll see, Blanche, the biological clock is very, very strong. As human beings, we don’t want to die, so what do we do? We make babies. That’s our passport to eternity!

⁂

—

What risks are we willing to bear?

This article was initially published in Issue 07 of BESIDE Magazine.

Get your copy now!This conversation left a funny taste in my mouth. A mix of veggie pâté and the end of the world. I felt like I was in a war without really knowing who the enemy was, without finding the weapons I needed to defend myself.

Still in shock, I spent the rest of my day walking in the Plateau-Mont-Royal, the neighbourhood where I grew up. I passed young parents pushing little pieces of eternity in their strollers. Was this really what I had always wanted, the unending continuation of myself?

⁂

I recently reconnected with one of my childhood friends, Simon. Simon is a dreamer—an active dreamer. He’s an architect who wants to change the system, remake its foundations.

He inspires me a lot. He makes me want to follow him in his dream. Simon tells me that the necessary tools are within reach: that we can create them ourselves and write a new story. He tells me about civil disobedience training courses and invites me to protests.

Simon has made choices that many would consider “extreme,” like the choice not to have children.

⁂

At La Barberie, in Québec City, Simon and Blanche are having a pint on the terrace.

SIMON—Right now it’s all so fragile. I can’t bring children into the world without being sure that it’s going to get better.

BLANCHE—Would you feel selfish?

SIMON—Yes. We’re in the process of leaving them with a debt that cannot be repaid.

The server comes to the table. Simon gets his credit card out of his pocket and holds it out.

SERVER—We don’t take credit here, sorry.

SIMON—Oh, okay.

He fishes in his pocket for some cash, and hands it to her.

BLANCHE—But are you saying that parents are nothing but heartless jerks?

SIMON—No, and that’s what’s contradictory! It shows our human incapacity of facing the gravity of the problem.

BLANCHE—This must not be something you speak about very often at family get-togethers.

SIMON—Actually, it’s becoming less and less shocking. Even my mother has accepted it.

BLANCHE—Oh yeah?

SIMON—Well, she would have loved it, that’s for sure—being a grandmother—but her ideas have changed. You should talk to your mother!

⁂

Which is what I did, that same night. I spoke to my mother and confided the fears that are taking up more and more space in my belly. And she spoke to me of the miracle of seeing the world through the eyes of a child.

My mother is always right; it’s almost annoying. Even when we don’t agree, she has the power to make things resonate in me. That night, an ember came into my mind and didn’t leave—a flicker that was fed by all the encounters and conversations I’d had during my research.

While it’s natural for fear to accompany awareness of a threat, the part I want to focus on is the awareness itself. I want to rub my worries against each other to produce sparks: to transform this energy into action. Children should be the driving forces for our hope, not the bearers of it. I want to think of them with each decision I make. We are taught from a young age to manage a bank account; we should also be taught about the immensity of the debt we are in the process of leaving behind.

But first I must learn how to reawaken my childhood curiosity, rekindle my sense of adventure, like the young audience members watching my parents’ plays, who look wide-eyed/astonished at each new day. I have no choice: I, too, need to find this treasure for myself. This is what will lead me to care for the world, to not take it for granted, and to fight for its survival.

I won’t give up in the face of such beauty.

This is the first task I give myself, as I wait to (one day, maybe) have children of my own.

A graduate of the Conservatoire d’art dramatique in Québec, Blanche Gionet-Lavigne is passionate about creation and social engagement. She recently collaborated on the documentary play Entre autres, presented at the Théâtre Périscope in April 2019. In addition to conducting a nearly two-year investigation into our inaction in the face of climate change, she also participated in the writing and performance of the show.