Stories

The Plan to Save Lake Kipawa’s Disappearing Trout

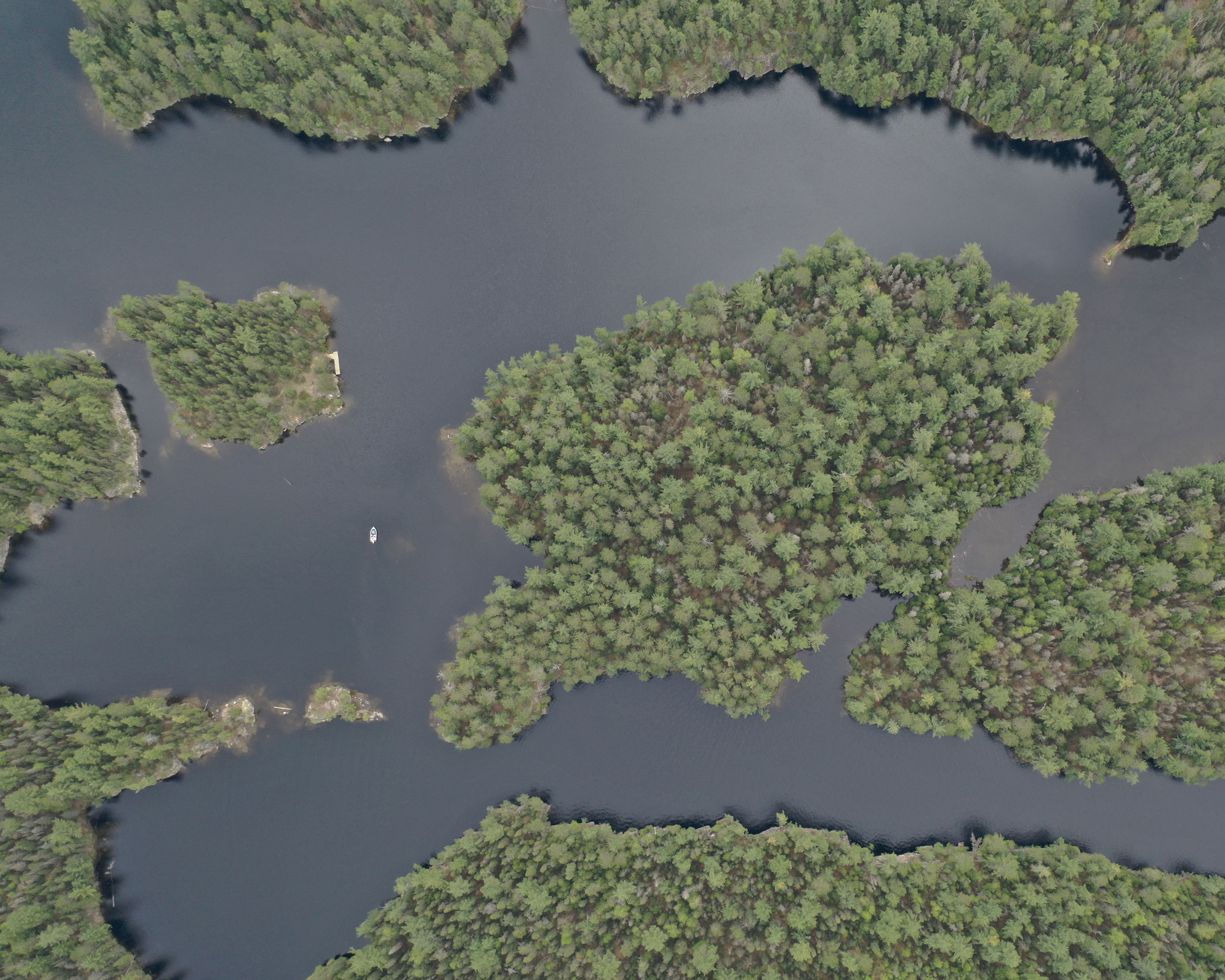

To reverse the decline of lake trout in the immense Kipawa reservoir in Abitibi-Témiscamingue, experts and locals must work hand in hand.

Text—Guillaume Rivest

Photos—Benjamin Rochette

In partnership with

Out in a boat on the Kipawa reservoir in Témiscamingue, Marc Girard shows me the secret spots where his father and his grandfather used to take him fishing for lake trout when he was a boy. The Girards have been spending their summers here for nearly five generations. Near a secluded island, he points out an authentic log cabin built by his grandfather almost 100 years ago.

The cabin, surrounded by old red and white pines, takes us back to another time, when the lake trout, a large freshwater salmonid also known as “touladi,” offered itself up easily as the main course for the evening meal. Today, these same spots are nearly devoid of the delicious fish.

After our visit to the lake, Girard invites me inside the cottage that has been his for the last 40 years. I notice an old fishing rod on display like a work of art. Its lead wire is a dead giveaway: it’s meant for lake trout, which, in a body of water like Kipawa, can weigh over 18 kg and tend to stay at a depth of about 30 m in the summer.

When I ask Girard if he still uses the rod, he gives me a discouraged look: “It must be 30 years at least since I used it. It’s not much use. There’s hardly any lake trout left.”

Girard, who is recently retired, rarely fishes on the Kipawa reservoir anymore. The lake, which was created in 1911 in the heyday of log-rolling, has changed a lot since his childhood. And even by then, the lake was very different from the one his grandfather described: filled with different species and surrounded by a multitude of rental cottages.

“When trout fishing started to decline, I mostly focused on the pike and walleye in the bay in front of my cottage. Even for this, I prefer to fish on other lakes now,” he tells me. The framed pictures on his walls are a testament to how much has changed: the 11 kg pike he holds proudly in one of the many photos seems to agree with him. Although their numbers have declined greatly in the Kipawa reservoir, images of lake trout can be found everywhere, a reminder of the importance they once held.

In spite of everything, Girard is hopeful: “I don’t know about all that the ministry is doing, but I know they’re working hard to re-establish the lake trout population. You can’t argue with that. I want my kids and grandkids to know a lake that resembles, even a little, the one I knew as a child.”

Colossal efforts

____

The future of the lake trout is also a subject of great importance to Martin Bélanger. Bélanger is a biologist specializing in aquatic fauna at the ministère de l’Environnement, de la Lutte contre les changements climatiques, de la Faune et des Parcs (MELCCFP). He and his team work on the Kipawa reservoir, stocking the lake trout for the year. In 2022, 44,000 young lake trout were released in the hopes of restoring the population to a level that would be able to sustain itself naturally.

“We’ll need to double the numbers of lake trout in order to consider the population sustainable,” Bélanger explains.

The truck full of trout arrives in the middle of the afternoon, right on time. André Fortin, a friendly fish farmer for the MELCCFP, has driven 12 hours to bring them to the place where they’ll spend their lives. Scooped by hand with a net, the fish are transferred into a basin of oxygenated water on a large aluminum boat, and then we head out toward the pools where they’ll have the best chance of survival.

These little trout have travelled a long way, but they are returning to the exact place where their ancestors once lived.

On Lake Kipawa, MELCCFP’s program aims to reintroduce the exact same genetic variety as the original population. In the fall, the MELCCFP team catches spawners of both sexes in order to collect and fertilize eggs, which are then transported to the government fish farm at Lac-des-Écorces. The fish develop in fish farms until they are a year and a half old and are then released into the same body of water their biological parents came from.

Seeing my surprise at the significant effort involved, Bélanger explains that it’s the best way: “In nature, the survival rate of a trout from egg to the age of one and a half is only 0.5 per cent. In fish farms, the rate rises to 75 per cent. A great number of lake trout are saved this way, while preserving the original genetic heritage of the Kipawa reservoir.”

A long-term project

___

Since 2014, biologists and technicians from the MELCCFP have spent nearly a month every year carrying out work on the Kipawa reservoir. Despite these efforts, the lake trout’s recovery to abundance won’t happen overnight.

“The trout we released today will reach sexual maturity in about 10 years,” Bélanger says. “Adding 44,000 trout to the lake doesn’t mean the fishing will be better by next year. This is really a long-term vision.”

To carry out an operation on this scale, collaboration, understanding, and patience from the local population are crucial.

“In general, people are aware that we’re doing a lot for the lake. They know it’s going to take a long time. Some people have more mixed reactions,” says Bélanger.

He recalls a time when two people confronted him, frustrated about the prohibition on winter fishing that’s been in place on the lake since 2014. “Some people are not happy. They want to be able to fish in winter on Kipawa, but with the scientific studies we have, we know it would be very harmful for the lake trout. It’s not a decision that was made arbitrarily. Studies and well-established scientific knowledge were consulted. We want people to understand and to be able to follow the evolution of the situation.”

The local population plays an important role in the species’ survival, and this is equally true of the people who manage the dam. For many years, 70 per cent of trout eggs died for reasons related to the variation in lake levels during and after spawning season.

“In 2013 we came to an agreement with the managers, so that the water levels would be consistent with the needs of the lake trout to reduce adverse effects on the eggs. In the coming years, we’ll evaluate the efficacy of this management by carrying out inventories and making adjustments as needed,” Bélanger explains.

More than just a trout

____

Lake trout is one of the most prized fish in Québec. For the tiny municipality of Laniel, a tourist destination for nearly a century, located at the tip of the Kipawa reservoir, fishing is absolutely essential for the survival of the village, which has been a tourist destination since the 1930s. On this lake alone, the economic benefits related to recreational fishing are estimated at $1.8 million. In addition to restoring the ecosystem, the MELCCFP is also trying to preserve the economic lifeblood of the communities near Lake Kipawa.

Serge Sayeur recently moved to Laniel. He and his wife bought the corner store and only campground. “We’ve bet everything on the Kipawa reservoir. We sold our house to move here. It’s the most beautiful body of water in Abitibi-Témiscamingue, and certainly among the most beautiful in Québec. We’re happy to see the MELCCFP investing so much energy in this corner of paradise.”

Sayeur is hard at work on improvements and has just placed the last screw in a new building under construction. The future of their business depends in large part on the quality of the fishing. “People who come here to fish make up more than half our clientele. The large majority of campers will throw a line in the water at one point or other.”

Then Sayeur says something that I feel like I’ve heard before, from Marc Girard:

“If we want future generations to know a lake that looks something like the one we know and love, we need to start taking care of Kipawa now.”

A collective effort

____

Restoring the lake trout population requires patience, and it also requires the active co-operation of citizens in collective efforts like carefully cleaning watercraft. Laniel has had a washing station for a few years now, and Bélanger and his team made sure to use one at the end of their stocking session.

The boat-cleaning stations can be found in several places throughout Québec to limit the propagation of invasive species such as the spiny waterflea, a small exotic crustacean in the zooplankton family, whose presence in Québec was confirmed in 2015.

Jean-Pierre Hamel, a biologist from the MELCCFP and specialist in the field, insists on the necessity of systematic cleanings: “If the spiny waterflea enters Kipawa, all our efforts to save the trout could be for nothing. Like a great sweep of a sword through the water.”

Once they’re introduced, there’s no way to remove them from a body of water, and the presence of the spiny waterflea deeply alters the food chain. “We do sampling for the spiny waterflea every year in the Kipawa reservoir, but it remains susceptible to contamination by this invasive species. The only defence we have is prevention and awareness.” And it is not only the introduction of exotic species that threatens the efficacy of restoration efforts. Since 2005 smallmouth bass have also been noted in the body of water, further complicating lake trout recovery efforts; the situation demonstrates the importance of understanding the consequences of our actions upon habitats.

An understanding of these issues is crucial for the sustainable management of waterways, in Laniel and elsewhere.

“If we want healthy ecosystems, everyone has to be part of the solution,” says Hamel.

As I listen to him describe this striking reality, I become aware that the health of a lake or river depends on a complex and fragile balance. Throughout my visit here, I’ve met people who consider the Kipawa reservoir to be a piece of heaven. The love for this place is evident all around. Travelling these shores, I, too, was struck by the beauty. I began to think about other lakes throughout the province that are proudly described by their residents as “the most beautiful in the world.”

Many of these bodies of water are also home to species of fish, like the lake trout, whose populations are in decline or at risk. In those places, as in Kipawa, the MELCCFP is making great efforts to protect both species and habitat, but I realize that the solution is in our hands: if we want to leave healthy bodies of water for future generations, we all must do our part.

Guillaume Rivest is a reporter and independent journalist originally from Abitibi-Témiscamingue. He holds a B.A. in applied political science and a master’s in environmental studies, and is passionate about nature and the outdoors. He contributes regularly to Moteur de recherche and Pénélope on Ici Radio-Canada Première.

The ministère de l’Environnement, de la Lutte contre les changements climatiques, de la Faune et des Parcs (MELCCFP) has, among other missions, the responsibility of promoting economic activities relating to wildlife while overseeing its conservation and that of its habitats. Ongoing work to re-establish the lake trout go back to the first recovery plan for the species in 1986. The current lake trout management plan has been in effect since 2014, and its teams follow the health of populations with great rigour and dedication. Additionally, MELCCFP contributes financially to the installation of boat-cleaning stations across Québec to combat the introduction and propagation of invasive species.

Never Miss Another Issue

Two issues per year

25% OFF previous issues

Free Shipping in Canada