Village

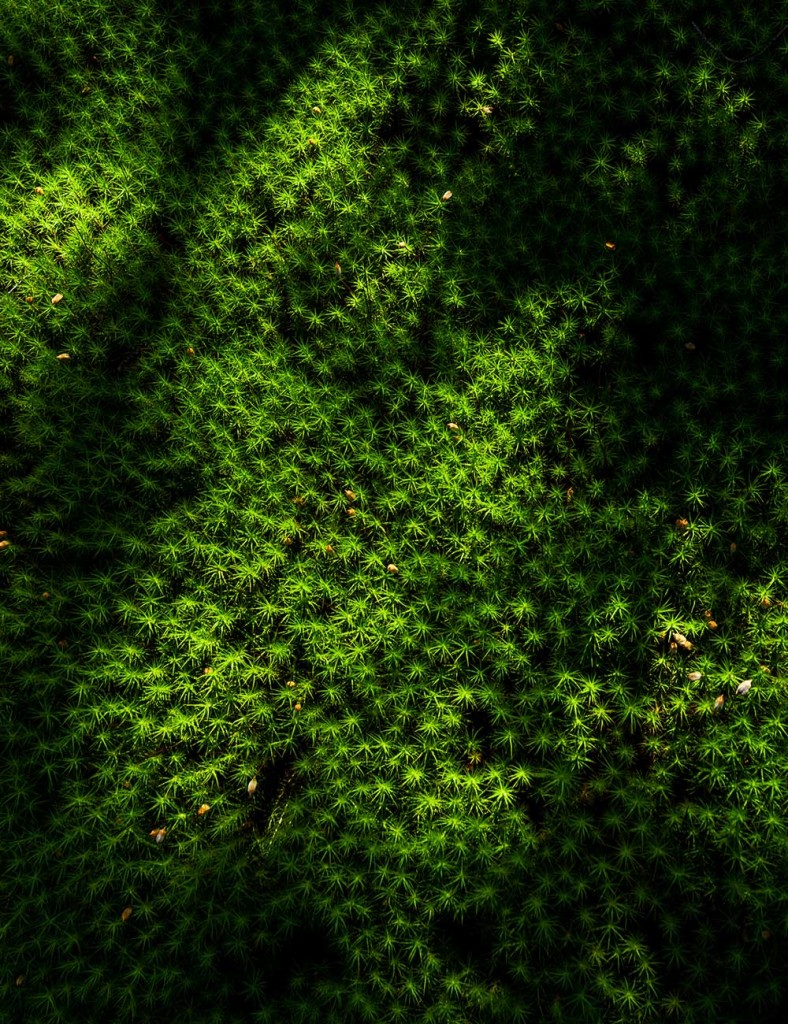

Sustainable Forestry Is Taking Root in Québec

Wood products have an important role to play in addressing climate change, but so do healthy forests. The Laurentian timber industry in Québec is maintaining this delicate balance.

Text—Valérie Levée

Photos—Arseni Khamzin

In partnership with

The Laurentians are a playground for outdoor and nature enthusiasts. Their hiking paths, mountain bike and snowmobile trails, ski slopes, and outfitters have a unique and irresistible charm.

But along with these recreational and tourist attractions comes development—both residential and recreational—and in order for new dwellings to be built, trees need to be cut down.

It appears to be a paradox: nature lovers are at least partly responsible for razing the forest that attracted them in the first place. Upon closer inspection, though, a thread of environmental concern guides the region’s approach to forestry.

Building with wood is a solution recommended by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) to combat climate change. “They’re trying to find ways to build a machine that will store carbon, but these machines already exist: trees!” says Samuel Royer-Tardif, a biologist and researcher at the Forestry Education and Research Center associated with the Cégep de Sainte-Foy.

Through photosynthesis, a tree turns CO2 into cellulose and other compounds, which are stored in its trunk and conserved, even after it has been transformed into planks. Building with wood, therefore, means storing CO2 in houses.

Of course, cutting down too many trees risks reducing the amount of CO2 captured through photosynthesis. For this reason, it’s absolutely essential that forestry is managed carefully, so that the forest can grow sustainably, continue capturing emissions, and supply our necessary building material.

The not-for-profit organization Signature Bois Laurentides was created to promote and synchronize projects among the forestry and wood transformation companies in the region. Making use of the forest’s inherent diversity, the selective harvesting of Laurentian forests is attentively managed for both the health of the planet and the enjoyment of the region’s many nature lovers.

Cutting so the forest will grow back

____

Since L’erreur boréale (Forest Alert), a 1999 documentary film that depicts swaths of decimated forests in Québec, practices have changed. Intensive cuts have certainly not ceased entirely in the boreal forest, but in the Laurentians, they’ve become rare. And a cut here does not systematically mean deforestation, if the forest is carefully managed so that it can grow back, in contrast to forests sacrificed to urban sprawl.

Public and private forests in Québec have now been entirely mapped out, with information about the nature of the soil, terrain, and waterways, as well as the species and age of trees. Using this data, the government’s chief forester calculates the allowable cut—the volume of wood that can be harvested while ensuring the forest is not cut down faster than it can grow back.

Only one per cent of public forests are harvested annually (according to a response plan created by the Ministry of Forests, Wildlife and Parks). In private forests, the harvests are lower, because owners are motivated by a variety of factors: some wish to preserve the habitat of deer or moose, for example, and others may simply want to maintain their woodland.

Current silvicultural approaches encourage the principle of ecosystem-based management, which imitates natural disturbances such as windfall, forest fires, or insect epidemics.

These disturbances create openings of varying sizes in the forest, which encourages the recovery of different tree species. “Pioneer species such as trembling aspen recover after forest fires or insect epidemics. Beech and sugar maple tolerate low-light conditions and tend to be favoured by small openings. Others, such as yellow birch, need an intermediate opening,” says Royer-Tardif.

The Laurentians are rich in walnut, ash, cherry, linden, and oak. “We need to create openings of various sizes to regenerate these species. Cuts that don’t open the forest cover tend to favour maple, beech, and pine,” explains Pierre Baril, executive director of the Coopérative Terra-Bois, which does maintenance work in private forests. Promoting this variety also increases wildlife biodiversity and provides ecosystems with greater resilience.

Forest operations are also required to follow guidelines for the preservation of soil, waterways, and sensitive areas, as written in the official regulations for the sustainable management of state forests.

“The government gives us forestry operation maps wherein everything is identified: waterways, traplines, standards that must be respected,” says Sébastien Crête, director of Groupe Crête. All these factors are taken into consideration by forest engineers who take steps to limit effects on streams and monitor potential consequences like erosion and sedimentation of waterways.

These practices, which have been in place in the Laurentians for a few decades now, are already showing results. David Armstrong, forest engineer at Terra-Bois, and Guilhem Coulombe, forestry director at manufacturing company Louisiana-Pacific, estimate that 10 years after a cut, you wouldn’t even be able to see the traces of the machines anymore. Partial harvests and rotating cuts allow the forest to regrow and mature.

A diversified ecosystem

____

In the 1980s the forest in the Upper Laurentians was mostly controlled by two companies, James Maclaren and Canadian International Paper, which, at the time, produced mainly newspaper from softwood.

“For them, the hardwood trees were considered weeds,” remembers Denise Julien, founding secretary of the Coopérative Forestière des Hautes-Laurentides. The government even created a plan to replace the hardwood trees in the Laurentians with softwood.

Forest management policies favoured the large companies and left only crumbs for small sawmills and wood processing companies. These smaller operations were frustrated with the softwood plan and wanted to work with all the species in the forest, says Julien. They successfully demanded that forest management policies be changed to protect the diversity of species and to grant access to companies of all sizes.

These days, Laurentian forestry mirrors the diversity of a healthy woodland ecosystem. Signature Bois Laurentides is a major reason for this change.

“We cover the whole of the chain, from harvest to the third transformation of the wood, and we get companies to work together to use the variety of tree species,” says Justine Éthier, the general manager. The result is a variety of products including a wide range of construction materials, from house framing to siding and furniture.

For example, Groupe Crête uses softwood to make sawn wood and exterior siding. Louisiana Pacific harvests poplar and beech to produce wood slats and assemble these into boards. The C. Meilleur sawmill specializes in white cedar. Commonwealth Plywood makes hardwood floors, Maxi-Forêt makes exterior siding, Uniboard makes particleboard, Mirabûches makes eco-friendly fire logs and animal bedding, Stella-Jones makes red pine telephone poles, Harkins makes log houses of white pine, and so on.

While the industrial ecosystem enhances the forest’s diversity, it also fights waste:

“We optimize resources. One hundred per cent of the raw materials that come from the forest and end up in the factory are used. Nothing goes to landfill,” says Sébastien Crête.

The logs are peeled and individually measured for length and width to maximize production of exterior siding and timber of various sizes. The chips are sent to White Birch Paper; the sawdust goes to Mirabûches and Uniboard.

As for the bark, it’s used to heat the factory, and the ash is sent to farmers to be used as fertilizer. A new niche is even emerging to synthesize biomolecules from low-quality wood with the aim of replacing molecules derived from oil, particularly in cosmetics.

When forests are well managed, the wood they provide can be used to its full potential as a renewable, environmentally friendly resource. In the Laurentians, this raw material supports a thriving diversity of companies and creates an environment where we can build our houses in good conscience.

Signature Bois Laurentides is committed to promoting the various wood products processed in the Laurentians. Created within the framework of the Ministry of Economy and Innovation’s ACCORD program, the network highlights a local and circular ecosystem of innovative businesses. These businesses focus on the renewal of forest resources and the full use of this ecological material, from the forest all the way to the final processing of the wood.

After completing her Ph.D. in plant biology, Valérie Levée turned her efforts to scientific journalism. She writes for L’actualité, Quatre-Temps, Prévention au travail, and FORMES, among other publications, on subjects as varied as health, botany, and architecture. She can be heard on Moteur de recherche on Radio-Canada and on Futur Simple on CKRL 89.1.

Arseni Khamzin is a visual artist and photographer based in Montréal. His work has been featured in a number of publications, including DER GREIF, Primal Sight (Gnomic Book), and Open House Magazine. He has also published two monographs of his work, JMZ and Matière première.

Never Miss Another Issue

Two issues per year

25% OFF previous issues

Free Shipping in Canada