Through the lens

Sumo Champions

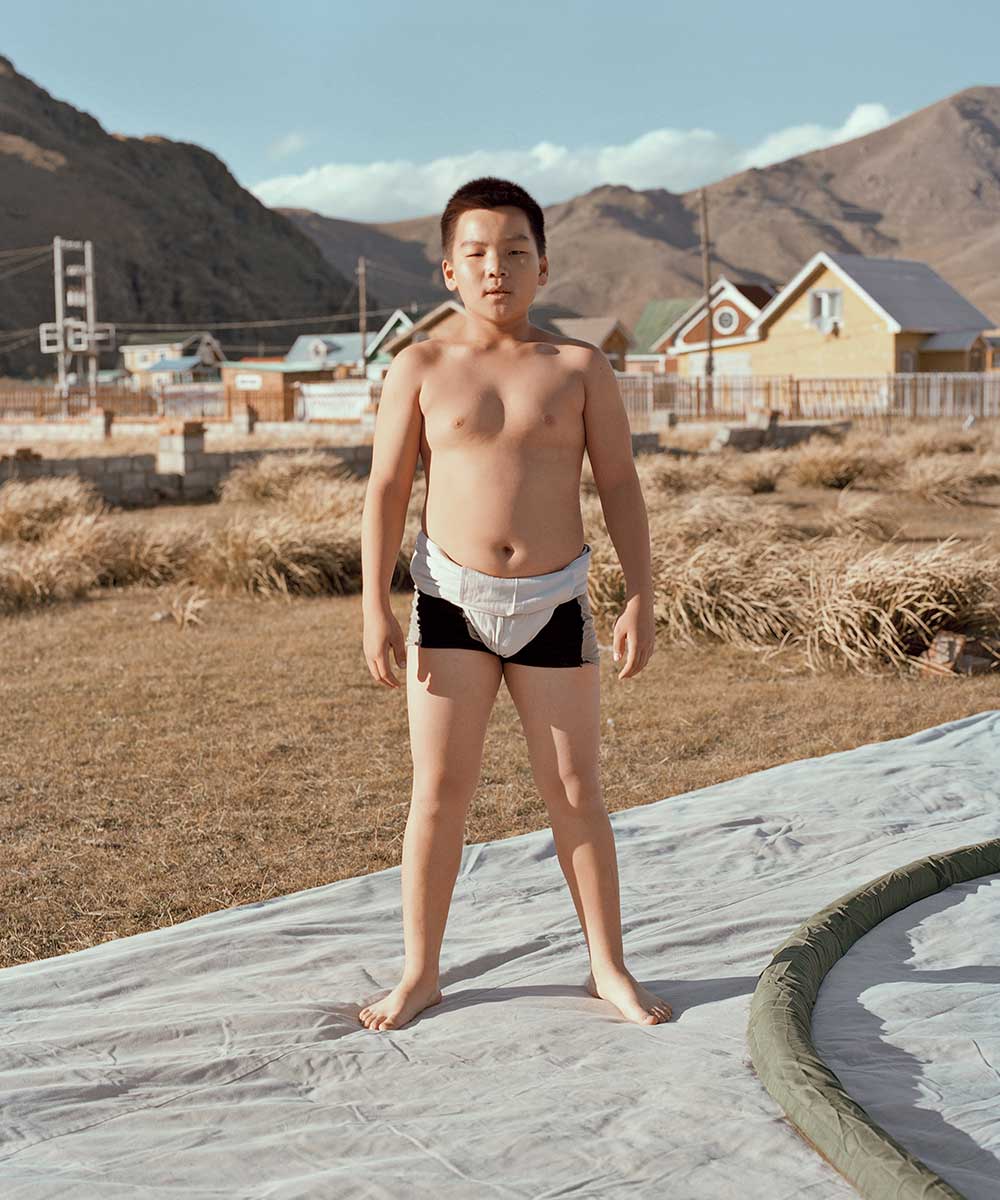

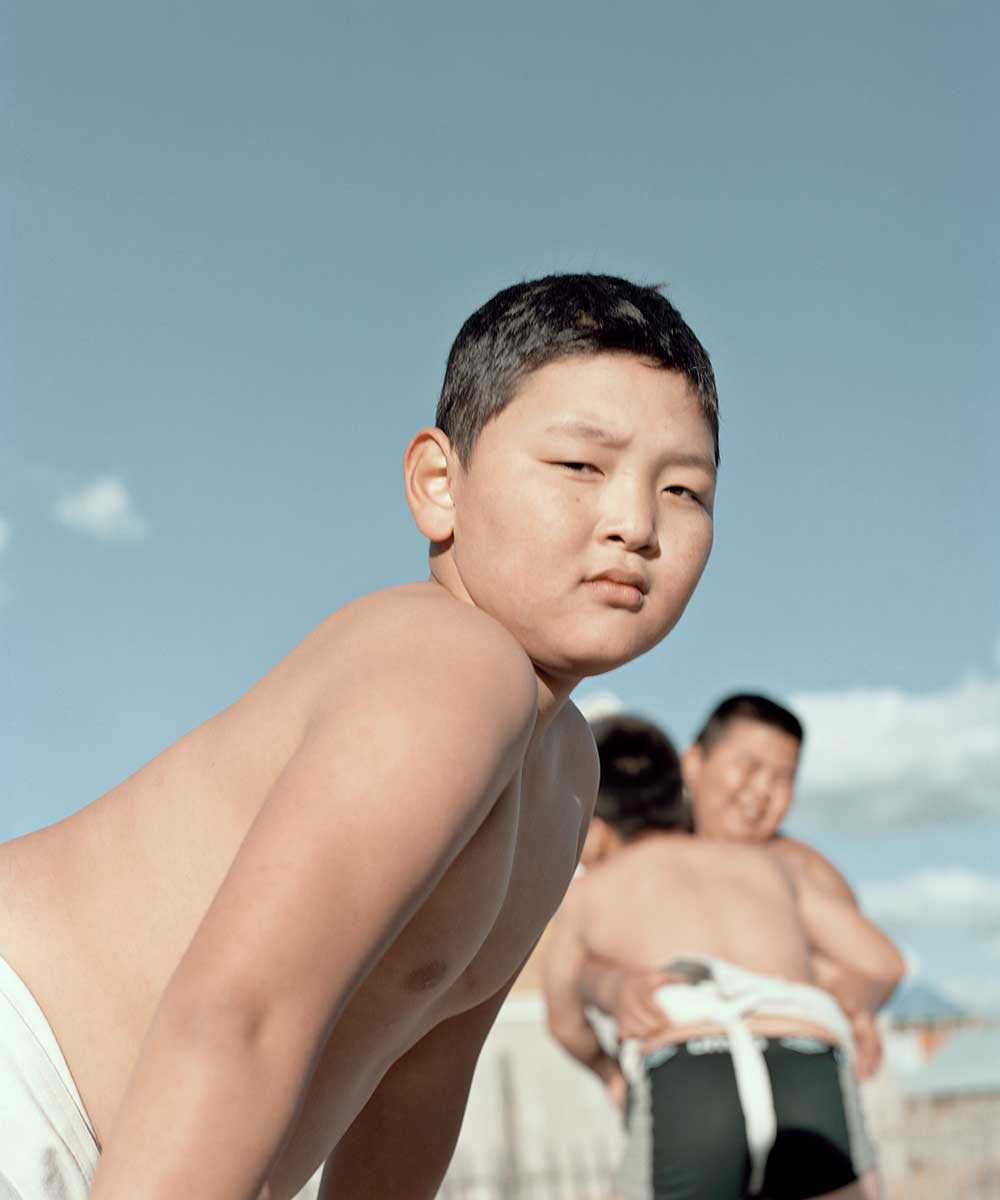

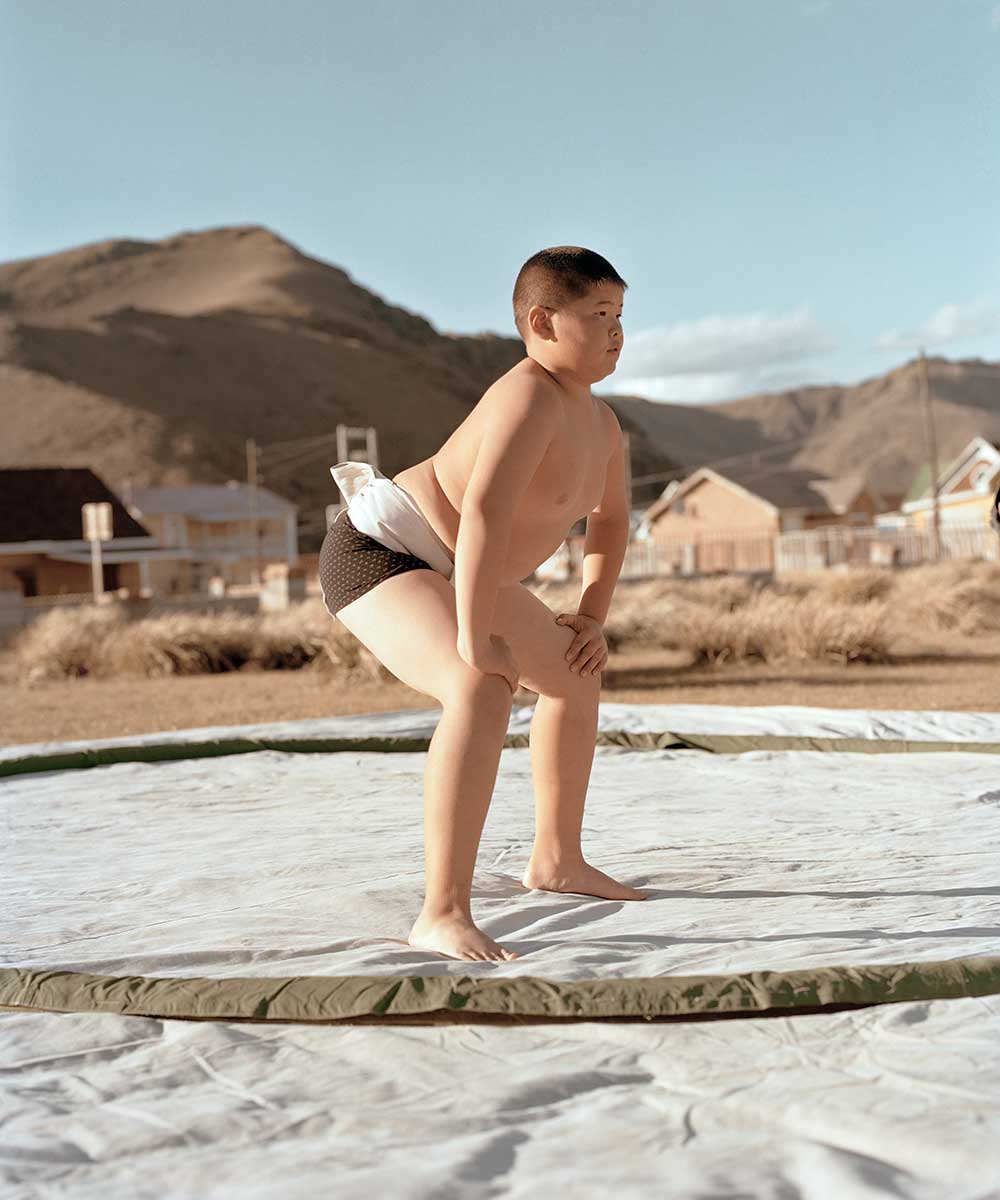

For nomadic Mongolian youths, sumo wrestling offers an unexpected path to success amidst their rough life on this fragile land.

Text—Colin Pantall

Photos—Catherine Hyland

How does a landlocked country with a population of three million manage to maintain its identity against the hypernationalism of neighbours like Russia, China, and Japan? This is the question that Catherine Hyland poses in her project Rise of the Mongolians on Mongolian sumo wrestlers, a sport that has been an astonishing success story for Mongolia.

Between 2003 and 2014, the country dominated sumo, providing successive champions (or yokozuna) in Japan. It’s a success that has made sumo wrestling a path to fame, riches, and a particular kind of glory for young boys in Mongolia.

Mongolia’s success at sumo wrestling lies in the history of the country itself. Wrestling is embodied in the national character, with ties back to Genghis Khan, Hyland discovers in an interview with Davaagiin Batbayar (who wrestled under the name Kyokushūzan Noboru), a sumo champion who has returned to Mongolia to pursue a career in business and politics. Batbayar believes traditional Mongolian nomadic lifestyles have contributed to the success of Mongolian wrestlers.

“While Japanese kids can just go and open the fridge for what they want,” he says, “Mongolian kids have to go get ice from the river, boil it into water, chop firewood, chop coal, make food, and ride their horse to the countryside to herd their livestock. Because kids wrestle naked in Mongolia they are usually adapted to wrestling in cold and hot weather, which gives them an advantage.”

Helping youngsters make this transition are training camps in Mongolia itself. Hyland photographed boys from the Kyokushu Beya sports centre training in a rural location in the Terelj National Park.

One image from foothills that surround the village shows how landscape and a sense of place are embedded in Mongolian lives. Ridged hills fall down onto a flat valley of scorched vegetation, a grassland through which a river and a road wind. But climate change has resulted in increasing desertification, the loss of grassland, and increasingly harsh winters.

The direct consequences of climate change have been experienced by these children, many of whom were born into nomadic lifestyles. They have bodies that are both bulky and muscular. “From the beginning they have a very active childhood, refraining from too much fat buildup, a lot of muscle build, and always keeping balance when riding horses,” says Batbayar. “Which also brings me to the types of food we eat. While Mongolians mainly eat meat and soup, Japanese tend to eat udon and white rice, which is why they have a lot of body weight, compared to Mongolians who have mostly muscle builds. Because Mongolians are high in muscle it gives them speed, and speed gives them the ability to do tricks.”

All the boys Hyland photographed now live in Ulaanbaatar, the nation’s capital, and many of them are from families who have recently migrated to the capital to endure the disastrously cold winters that have devastated the herds of livestock they once tended to survive.

The resulting influx of people has changed the geographic landscape of the city into a patchwork quilt of Soviet-era tower blocks and parcels of land filled with the gers (or yurts) of recent migrants to the city.

These changes are causing economic and environmental changes to the city (Ulaanbaatar has some of the worst spikes in air pollution in the world), but despite this the city still remains a major source of combatants for the Japanese sumo wrestling industry.

“Once a Japanese reporter visited and was astonished,” says Batbayar. “He said it’s very weird how in Ulaanbaatar a little over one million people reside, and that all the great Mongolian sumo wrestlers are basically from the same neighbourhood. It was then that I realized that it was very weird how a few kids from the countryside who had a mere interest for the sport could be dominating sumo champions.”

If the first step in becoming a sumo champion is, as Batbayar puts it, “… crawling in the sheep enclosure, carrying ice, chopping firewood, riding horses,” the training camp is the second stage. Succeed there and what lies beyond are the hard rigours of life in Japan, with constant training, limited communication with family from home, and the need to become fluent in Japanese. Before you can even train in Japan, though, you need to really prove yourself as a wrestler.

“Nowadays there are regulations in place for the 50 sumo schools in Japan that regulate the amount of foreigners one school can hold at once, which is at this time one foreign student per school,” says Batbayar. “This is why many kids who have the spirit and the skill it takes to be a very good sumo wrestler can’t get in, as you also need to be a certain age. I believe that if we were to ignore these regulations and took the best skilled and the hardest working from all 21 districts of Mongolia, the top 20 best wrestlers would be Mongolian.”

Catherine Hyland is an artist based in London. She graduated from Chelsea College of Art and Design with a First class BA (Hons) Degree in Fine Art and completed her Masters at the Royal College of Art. Her photography centres around people and their connection to the land they inhabit. Primarily landscape-based, her work is rooted in notions of fabricated memory, grids, enclosures, and national identity.

Issue 05 Cover Story: Atacama Desert

Catherine Hyland created the cover photo of BESIDE Issue 05: What does ouf future with nature hold?, showing a lithium mine in Chile's Atacama Desert.

Never Miss Another Issue

Two issues per year

25% OFF previous issues

Free Shipping in Canada